to the city. And Moag was his man.

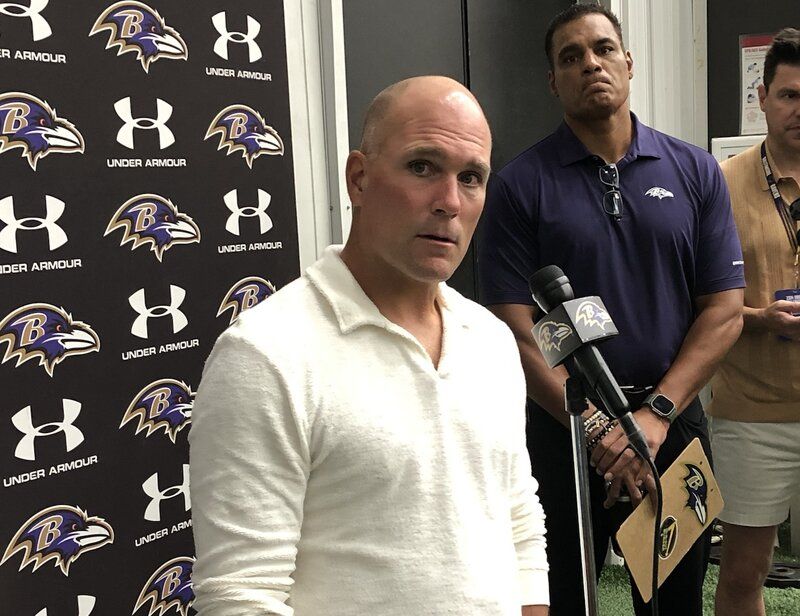

Moag made initial contact with Bailey in February 1995 and was immediately rebuffed. “My first phone call was flatly rejected,” Moag said.

By late July, Moag was sizing up all of his options, including suing the NFL for antitrust in the expansion process. That certainly got him attention at the league’s offices on Park Avenue in New York.

Moag enlisted Frank Bramble, a banker with Baltimore ties, to get the ear of Al Lerner. Moag brought forth the facts and figures about the Baltimore stadium situation and made it very clear to everyone that he was going to get a team. The deal was too sweet, much better than any of the existing teams were ever going to get in their current cities. Someone would snap it up.

The days of Herb Belgrad bringing crab cakes and sunshine to the NFL and its owners were over. “We had tried the carrot and it didn’t work,” Moag said. “This time we were bringing the stick.”

Ironically, it was at an Orioles game, the night of Cal Ripken’s famous 2,131st consecutive game on Sept. 6, 1995, that Moag and Lerner got serious. Less than two weeks later, on Sept. 18, Moag was in New York City with the Modells, Lerner, Bailey and initial contract ideas.

In early October 1995, here were the options of Arthur B. Modell:

- Stay in Cleveland in a renovated, antiquated stadium with the current debt service and very little financial wherewithal to compete for a Super Bowl.

- Sell the team to another interest completely, perhaps Lerner. Even in selling the team, with the current stadium situation and the debt, the team was nearly worthless because of its arid revenue stream.

- Move to Baltimore for a sweetheart deal, a new stadium and new revenue streams, keeping the team in his family for the foreseeable future. At the very least, it would make the franchise infinitely more valuable as a saleable product down the line.

Just to make everyone in the process a little nervous and to maximize his leverage, Moag flew to Arizona in early October and began paging key personnel with the Browns, the Bucs and the Bengals to a number in the 602 area code to prove he was chatting with Bill Bidwill.

Moag, no stranger to leverage and lobbying, pulled it off.

On Oct. 27, 1995, on Lerner’s private jet on the tarmac at BWI Airport, Glendening and Moag met with the Modells, Lerner and Bailey to seal the deal.

Despite the best intentions on both sides – and some binding language in the contracts – the desire to keep the Modells’ intentions to move to Baltimore private was unsuccessful as word leaked quickly. A press conference was called in parking lot D of the Camden Yards complex to announce Art Modell’s intentions to move the Cleveland Browns to Baltimore.

I asked the first question to Art Modell.

“When the team comes to Baltimore, will you call the team the Baltimore Browns?” I asked.

“Yes,” Modell said. “They will be the Baltimore Browns.”

Modell, in the aftermath of the unbelievably messy media circus created by the move, had already decided to give the name and colors back to Cleveland long before he had ever arrived in that parking lot. The NFL wouldn’t allow him to make that announcement. He had to hold the Browns name for leverage down the line. It was solid advice from Park Avenue because he would eventually need it.

In the ensuing mess that followed the Nov. 6 announcement (the Cleveland and national media, Browns fans around the world and the crafty use of the Internet created a firestorm) came the realization that he would need league approval. And it almost didn’t happen.

There was a tremendous movement afoot to keep the Browns in Cleveland and grant Modell an expansion franchise in Baltimore that wouldn’t begin play until 1999.

It took the league, Cleveland politicians and the Maryland government more than three months to clear the way for the Modells to set up shop in Baltimore and begin doing business. Even in clearing the way for the new stadium in Baltimore, there were many opponents of using state money to fund the facility. “Brains not Browns” signs and pins (some wanted the money spent on schools and education instead of football) were scattered throughout Baltimore by those who didn’t understand the economic and civic impact of the NFL.

My friends and I certainly understood the impact of having a team in town. We just couldn’t follow a solid lead when we had one.

As much as WBAL’s Mark Viviano is credited with breaking the story of the Browns moving to Baltimore, I was the first one who stumbled upon the story. Or more, accurately, it was my best pal Kevin Eck, who worked as a copy editor at The Baltimore Sun.

In late October 1995, while covering the World Series in Cleveland, I brought Eck along to have a traveling and peanut-eating companion.

In anticipation of Game Four, held on Wednesday, Oct. 25, 1995, I left for the ballpark early to do my radio show. Eck stayed behind, said he was going to drop by the then-new Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and meet me at the ballpark closer to game time.

When he arrived that evening, he spun a wild story to me during the early innings of the game.

He arrived at the Hall around 4 p.m. only to be told it was closed due to a private party for the World Series. Not knowing how far Jacobs Field was, he hailed a cab to the ballpark. In that six-block ride, the cabbie engaged him in conversation.

“Where are you from?” said the hack.

“Baltimore,” Eck replied.

“Hey, you guys have a football team!” the cabbie said.

Eck, startled, said, “Yeah, we have the CFL now. The Colts left a long time ago.”

“No, not the CFL,” the cabbie continued. “You’re getting the Browns.”

Eck said the cabbie turned to him and got a wicked look in his eye.

“You may think I’m outta my mind right now and that I’m just some stupid cab driver,” he said. “But the Browns are moving to Baltimore and Art Modell has already signed the deal. My neighbor is on the Browns’ Board of Trustees and the deal is already signed. I know, I know. Right now you think I’m crazy, but you’ll see. The Browns are coming to Baltimore. Just remember where you heard it.”

For a $2.85 fare, Eck got a million-dollar news lead and a ride to Jacobs Field.

Later that night, while at a club in Cleveland’s suburbs, my best pal and I laughed like hell over a beer about the Browns coming to Baltimore and what a silly

(NEXT)