Pittsburgh boss and then-Marlins skipper Jim Leyland. Leyland loved Wren and told Miller he’d be a perfect candidate. Wren was selected over White Sox assistant GM Dan Evans, Braves assistant GM Dean Taylor and Indians assistant GM Dan O’Dowd.

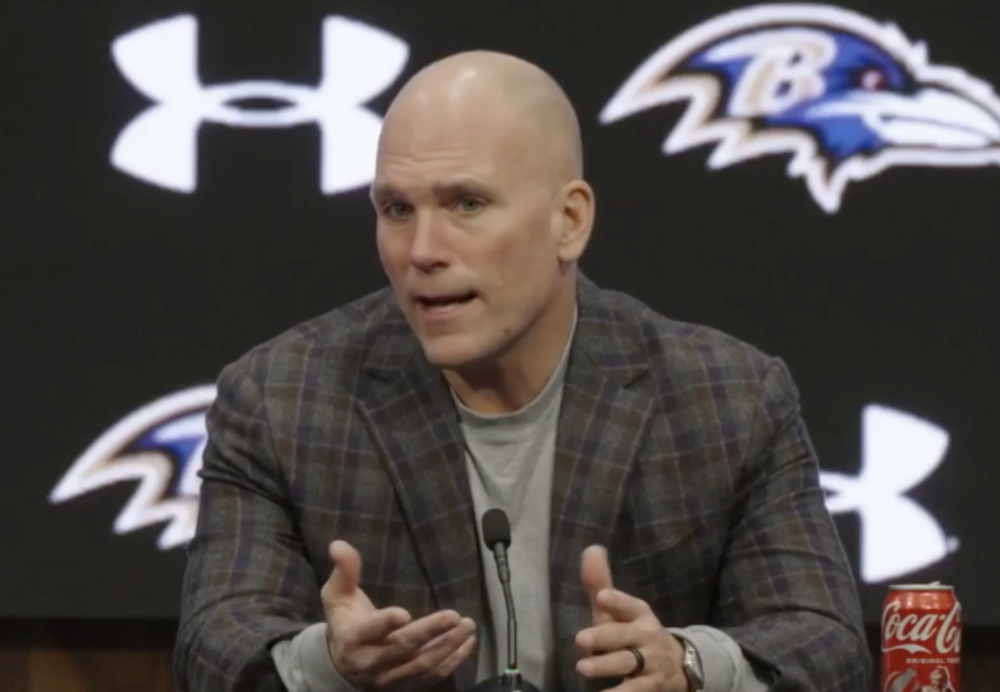

Wren was immediately peppered by the media about his input and control on baseball matters given the track record of Angelos in Baltimore with a legendary baseball evaluator like Pat Gillick. “He said he would leave the day-to-day running of the ballclub to me,” Wren said at his hastily arranged press conference at The Warehouse, where team president Joe Foss held court. Angelos was never present at press conferences to announce new Orioles front office staff or managers. “But anything of major importance – just like the other 29 ballclubs – you’ve got to run that by ownership,” Wren conceded. “Peter and I both asked hard questions of each other.”

Foss insisted that Wren had power. “I think there was a comfort level in believing he would be a positive team player,” Foss told The Sun. “That does not suggest a ‘yes man’ but rather someone who can speak his mind and participate in a decision-making process.”

Wren said he was given assurances he would be free to name his own assistant general manager, director of scouting and director of player development. Wren agreed to retain Ray Miller as manager for 1999 but believed the manager was a subordinate who answered to the GM. Wren was also told that director of player development, Syd Thrift, would remain in the organization but would be assigned to another capacity. Thrift, meanwhile, always privately had and held the ear of Angelos, even in his newly and temporarily diminished role as a special assistant.

Wren inherited a team that had greatly disappointed in 1998 while leading MLB in money doled out in player salaries. And, still clearly obsessed with winning, Angelos made it clear he was prepared to spend even more to prevent the New York Yankees from repeating as World Champions in 1999.

But the Yankees were on the verge of changing the paradigm for how MLB teams would be funded in the new century. Steinbrenner and his staff were busy forming a regional cable sports network with the New Jersey Nets that was to be called the Yes Network. The Yankees were awash in cash from having won two World Series in the previous 12 months and the residue was a payroll that went from $65 million in 1998 to $88 million in 1999. George Steinbrenner wasn’t just back from his exodus from Major League Baseball – he was delivering championship flags and parades in The Bronx again and wanted more.

But the Yankees were having a legitimate problem negotiating with local hero Bernie Williams and were floating the idea of signing Albert Belle, who had a stipulation in his contract with the Chicago White Sox that he be paid in the top three of all MLB salaries or his contract could be voided. When Belle demanded that money in the Fall of 1998, the Sox balked and let him walk after two monster offensive seasons on the South Side.

Angelos, paranoid by his very nature, was convinced that the Yankees were about to continue a spending spree and leaped to grab Belle from the open market before he landed in pinstripes. Steinbrenner told Buster Olney of The New York Times just days before: “Can we handle (Belle)? I believe we can. It’s what my manager wants and my general manager wants. I have no fear about it.” Meanwhile, manager Joe Torre had a long chat with Belle and reported: “It looked like he was very interested in us. He was easy to talk to.”

The Boston Red Sox, who hadn’t won a World Series in nearly a century, were also making a hard push for Williams, and long-term deals and millions of dollars were at stake.

At the time, Wren and the Orioles were in high speed pursuit of local outfielder Brian Jordan, who was wined and dined by the team and walked into Camden Yards to see his name and image and stats on the scoreboard in centerfield. Wren believed the Milford Mill grad would want to come “home” to Baltimore. The only problem was that he lived in Atlanta, where he moonlighted for the Atlanta Falcons as a two-sport NFL safety and loved it in Georgia. Plus, the Braves said they would match any other offer for Jordan, who had been a standout for the St. Louis Cardinals. Jordan had a lingering back ailment and this was the first offseason that Angelos became quite interested in how player contracts and injuries can be manipulated during negotiations. Forever the lawyer, Angelos saw these health concerns as loopholes in the negotiating process to minimize downside risk with brittle baseball players.

The guaranteed money had gotten to be astronomical, something that Angelos never really understood given the restricted market and short life span of a baseball player. The open MLB market and the wealthiest bidders always seemed to be driving up costs in an astounding way vs. the rest of the common marketplace in America. It unnerved Angelos – the rising costs of salaries, which weren’t commensurate with the rising cost of living adjustments in the rest of