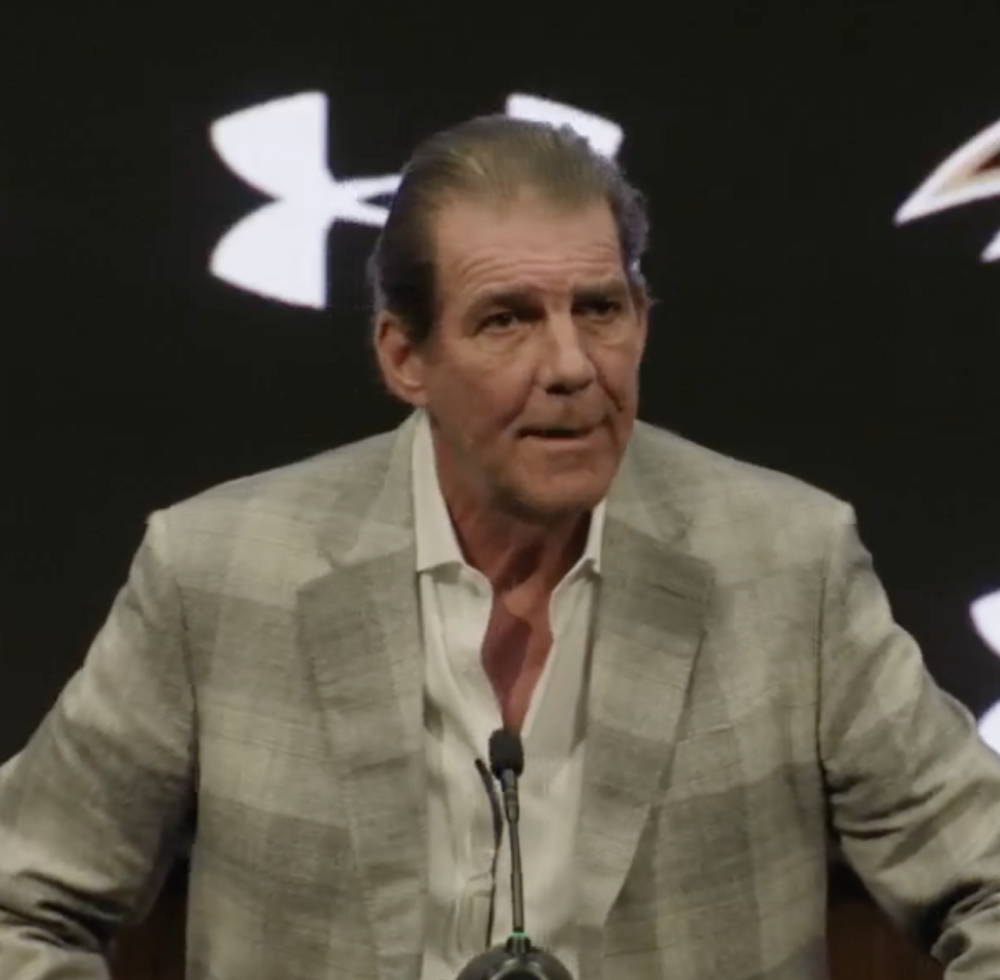

Many times he spoke with great pride about establishing the “Inner Circle” group in 1982 with then-head coach Sam Rutigliano. The Circle was an anonymous player support group for alcohol and drug dependency that became a model program for all sports franchises in America. Modell cared about his players.

As his stature grew in Cleveland so did his ability to give back to the community. Even his detractors on the Cuyahoga couldn’t deny the tens of millions of dollars the Modells helped raise for the Cleveland Clinic, the Hospice of Western Reserve, and their donations to the arts, led by Pat Modell for the better part of three decades, a tradition they would continue in Baltimore.

But the older his stadium got, the more upscale the rest of the Cleveland sports scene became. First it was Jacobs Field and then Gund Arena came in 1994. Plus, the new maverick ways of the Jerry Jones-style of NFL local marketing and revenue generation was coming, and Modell quickly started sinking in debt. The revenue streams that guys like Bob Irsay took advantage of in new stadia were starting to dramatically affect Modell in several ways. It really was a cocktail of economic issues. Rising costs. No way to generate more local revenue without raising ticket prices. The fans wanted a championship. And his competitors were outspending him. And more than even making money, Modell wanted to win.

As early as 1993, Art Modell realized his financial situation wasn’t improving and couldn’t improve without a massive dose of the kind of civic support that the Indians and Cavaliers had received from the city and state. If there was every any doubt about how bad the situation was, at one point Modell asked the Cleveland city police chief to deliver a message to get the mayor to call him. Mayor Michael White delivered a message back to Modell two weeks later that there would be no meeting about anything regarding a new stadium. Modell, almost in tears, knew his fate would reside elsewhere and that Cleveland would hate him.

But Modell had few options in 1995. He refused to sell the team because he’d still wind up in bankruptcy without winning a title. Newsome has said on numerous occasions that not winning the Super Bowl affected him greatly in Cleveland. It ate at him. He spent money he didn’t have trying to bring Browns fans a championship trophy. By the summer of 1995 he was nearly $300 million in debt because the Browns were losing $20-$30 million per year, and it was eating at whatever equity Modell had in the franchise, that was playing in a dump on the banks of Lake Erie.

Modell was trapped. His debt was nearly $300 million. His team was barely worth $300 million. The Browns had an arid revenue stream once Jacobs Field and the Gund Arena began selling fancy skyboxes. Art barely had running water at Cleveland Municipal Stadium, and he was desperate. Sure, he could sell and leave as an utter failure. He’d be broke, without the team, without a championship – not the legacy he was looking to leave for David, John, and his estate after essentially being one of 10 men who literally built the greatest sports league known to modern man. Arthur B. Modell helped create an industry generating billions of dollars in revenue that never seemed to come his way. He couldn’t just walk away.

Modell knew hard times. He’d been broke once and wasn’t going to endure it again. So, on a tarmac at Hopkins International Airport, he boarded a plane for BWI and signed to move the Browns to Baltimore in October 1995. Maryland Stadium Authority chairman John Moag made the deal of a lifetime for both parties. The complexity of the move has filled two books – one on the Cleveland side called, “Fumble” and one on the Baltimore side, called “Glory For Sale: Fans, Dollars and the new NFL” – and is covered extensively in “Purple Reign: Diary of a Raven Maniac.” Somewhere amidst the stories – the tears, threats, political wrangling, and subsequent lawsuits, the truth remains: the Baltimore Ravens were born.

And from a tangled garden of weeds and thorns came a rose.

A shining purple rose in vibrant colors for the people of Baltimore and for its local pride. The Ravens have become a civic institution and have earned their place. But it didn’t come easy, the birth of the franchise.

“This has been a very, very tough road for my family and me,” Modell said after arriving in Baltimore. “I leave my heart and part of my soul in Cleveland. But frankly, it came down to a simple proposition: I had no choice.”

So many of the good parts of the Ravens that have won two Super Bowls in 17 seasons stepped off that original bus that arrived from Cleveland.

It’s that institutional memory created by experience and wisdom that aids the franchise every day in so many decisions. Lots of mistakes were made by the Modells in Cleveland – with the government and political leaders, with the media, with the fans. In Baltimore, they would do it differently.