In 1996, Baltimore was in love with Cal Ripken and the Baltimore Orioles, and Modell’s stained NFL team in purple uniforms were not universally revered. He was reviled nationally in the media for the move and the death threats, banners flying over the stadium with derogatory comments, and the constant stigma of the move ate at his soul.

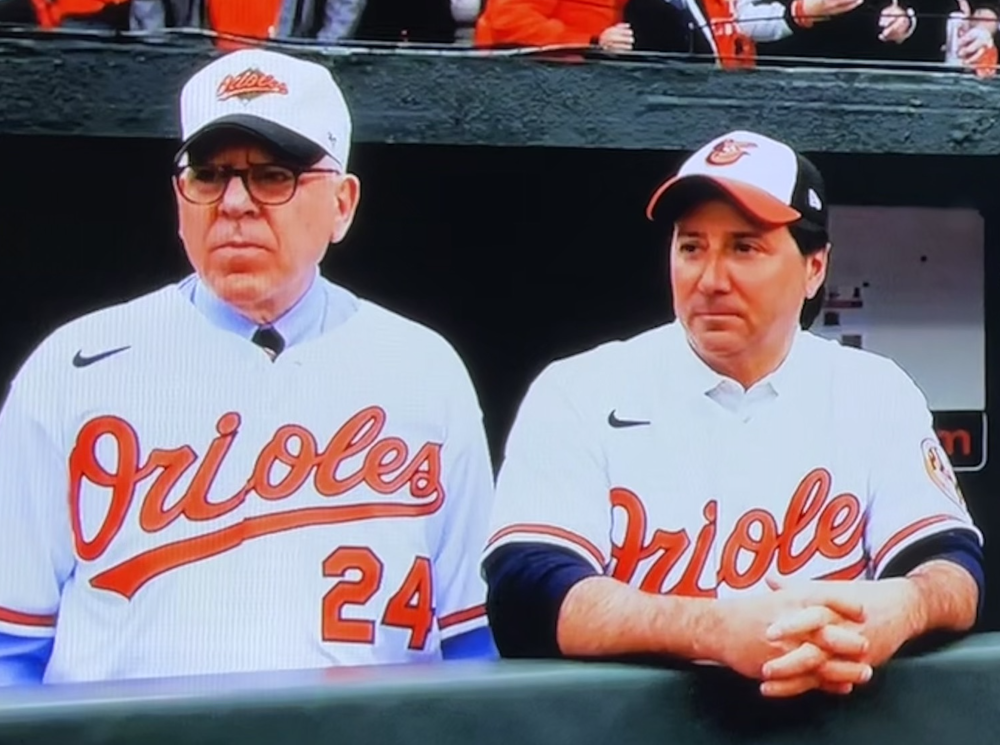

Despite the move, his debt was too deep, his financial troubles were simply too steep to overcome. Bisciotti made the deal to buy the team in late 1999 and by 2004, Modell moved to the background as an emeritus owner who left with complete respect, access, and family treatment with a permanent office in Owings Mills. Bisciotti always thought of Art as a confidant, someone who knew what it was like to be an NFL owner and sought counsel with him throughout the relationship. Steve knew that Art knew quite a bit more than show business. He could spend $600 million on the team but he couldn’t buy Art’s institutional knowledge.

The Super Bowl XXXV run in January 2001 was Modell’s shining moment and the pride and joy of his lifetime of work in the NFL. He got to hold and hoist the Lombardi Trophy. Like Ray Lewis, Art loved the confetti, too. Art was so happy that night.

“I don’t look back with any regrets,” Modell said then. “I’m grateful for my life. My life was nip and tuck too many times and I was able to survive. If I’m a survivor, I want to be a survivor health-wise, and I want my family to survive, my grandchildren. I live for my family. My wife, my sons, their wives and, above all, my grandchildren.”

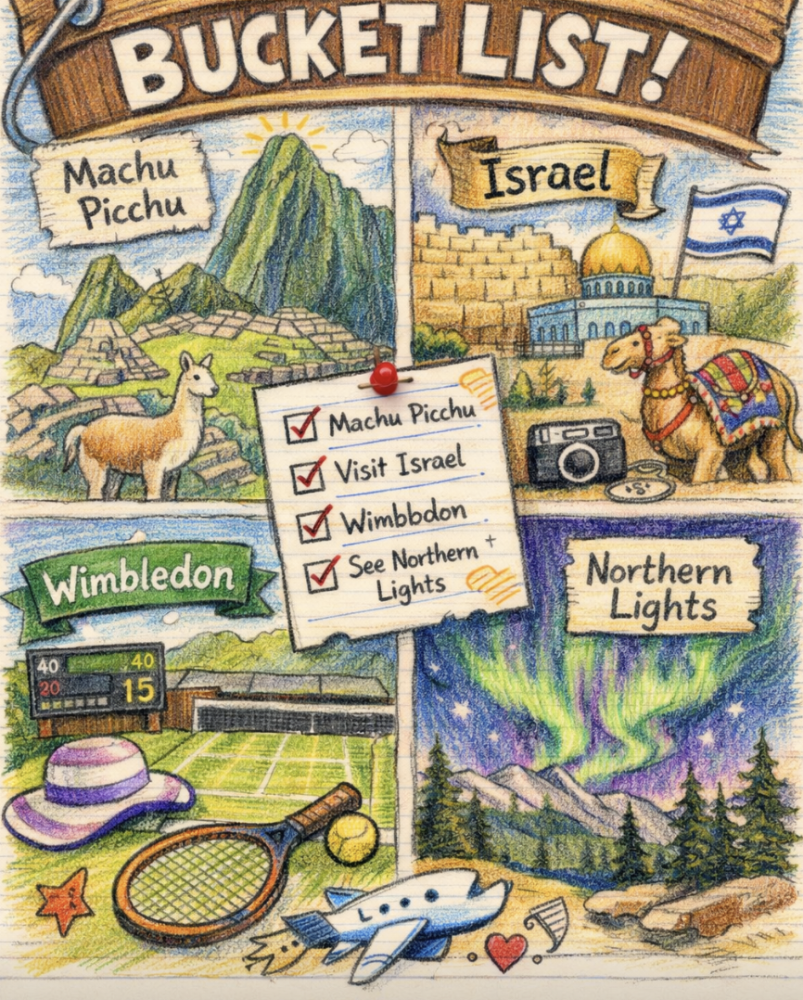

His tearful speech in the locker room was a culmination and a vindication for all of the pain, blood, sweat, and tears for him and his family. After all, he was part of the group of men who invented the Super Bowl. He was the incoming president of the NFL when the game was dreamed up and named by Rozelle’s daughter in the late 1960s. And he spent 35 years trying to win it. It was part of his identity, part of his lifelong dream, part of his personal Manifest Destiny.

It wasn’t on the bucket list.

It was the bucket list.

He danced with Ray Lewis at City Hall in Baltimore in a World Championship parade just five years after leaving Cleveland amidst scorn and a storm of hell and fury for having not won a Super Bowl.

In 43 years of ownership, Modell’s teams made 28 playoff appearances and had an overall record of 347-305-8 with two league championships and an NFL title in 1964.

And Art Modell helped so many people along the way to that Super Bowl win in 2001. He reveled in taking many of his trusted employees along for the ride.

In addition to Ozzie Newsome, Pat Moriarty, and Kevin Byrne on the football side, there were also a handful of others like Bill Jankowski (information technology), Bob Eller (operations), John Dubay (video), Vince Newsome (pro personnel), George Kokinis (personnel and scouting), Mark Smith (head trainer and longtime assistant to Bill Tessendorf) and P.J. Patel and Bryan Filkins (groundskeepers) who all made the trip with Modell from Cleveland, and remained through Bisciotti’s ownership. They were with the team in New Orleans when the Ravens won Super Bowl XLVII in 2013 to go along with the Super Bowl XXXV win in Tampa in 2001. They had come full circle.

Perhaps no one was closer to Art Modell than Byrne, who started in 1981 as a public relations man who came from TWA Airlines after a few years with the St. Louis Rams in the Jim Hart-RogerWehrli-Dan Dierdorf days.

Byrne began his career at Marquette as the sports information director for legendary head coach Al McGuire in Milwaukee, where he was also best pals with assistant coach Rick Majerus during their 1977 NCAA Championship run. Byrne had been through every coach, every free agent, every quarterback, and every loss with Modell and Newsome for more than half his life. Byrne is truly the conscience of the Baltimore Ravens – the historian, the trusted right arm for Modell, and now Bisciotti on the communications side of the franchise.

Byrne was there for all of it – 32 years of everything the Ravens are or ever were. He now has two Super Bowl rings in Baltimore after a lifetime of disappointment in his hometown and birthplace of Cleveland. He’ll write a great book one day, or should. From Howard Cosell stories to Jim Brown tales to Pete Rozelle chats to the private thoughts of Art Modell, Byrne is an encyclopedia of football information.

Bob Eller might be the best Baltimore football story you don’t know. Eller, who does all of the Ravens’ planning for road trips, hotels, airlines, plus a myriad of other roles for the team and its staff, was actually an intern in public relations for the 1983 Baltimore Colts as a senior at Towson State University. He was a local kid and hoped to land a fulltime job in early 1984 when, instead, Irsay brought the Mayflower vans to Owings Mills on that snowy night of March 28th. Like everyone else in Baltimore, he watched the vans move out on television and wept.

“I was crushed,” he said. “Along with everyone else, I loved the Colts. I lost the team and I lost a job.”

Seven weeks later, Eller received a call from Pete Ward, who had made the move from Baltimore to Indianapolis with the Irsay family. Ward, who still works for Jim Irsay and the Colts, offered Eller the job he was waiting for in Baltimore and Eller grudgingly decided to go to Indiana to join the Colts staff. It was a rare find for a sports job because NFL teams employed fewer than 50 full-time workers in those days. When another Baltimorean and ex-Colts staffer Ernie Accorsi emerged as the new general manager in Cleveland the following year, he summoned a more seasoned Eller from the Colts to work for Modell and the Browns in Northern Ohio.

That was 1987. In 1995, Modell told Eller he was moving his franchise to Baltimore, returning him on a mystical football journey back to the land of pleasant living and his home. Like the rest of the aforementioned who have been in Baltimore over the past 17 years, Eller has two Super Bowl rings and a lifetime of Modell stories.

“It’s a tribute to Art and what kind of organization we’ve had by the people who’ve been here, but also now work in other businesses or around the league,” Eller said. “It’s just a solid mentorship and solid leadership. We all saw right away the way to go about things. It starts with Art, and it was passed along to Steve and encompasses his principles, which aren’t much different from Art’s.”

And as much as he remained loyal to many front office and behind the scenes personnel, it was Modell’s relationships with football players and his adoration of their toughness, commitment, and will to win that could be written and set to music in the glorious pageantry and style of NFL Films. Of course, the presentation of the game of football and its players as “mighty men” was patently endorsed and applauded by Modell. He loved the theatre of the sport and the gladiatorial portrayal of its competitors on the gridiron. Modell was on the original committee when “Big” Ed Sabol walked into NFL commissioner Peter Rozelle’s office in an attempt to bring the game on the field to life in film.

Certainly, NFL Films portrayed no one as more larger than life or treated with more reverence than Jim Brown, who was Modell’s first superstar player and a lightning rod for attention. Many would simply say that Brown was the best player to ever wear cleats. and it’s very difficult to argue otherwise given his stature with the Cleveland Browns and in the NFL as a living legend. Brown, who was also a world class lacrosse player at Syracuse in the early 1950s before coming to Cleveland, was an iconoclast in many ways – controversial off the field, getting deeply involved in Hollywood and acting, and eventually leaving football and Modell in his prime at the age of 29. They held deep respect for one another all of their lives despite having many public differences of opinion over the years. Modell cared about relationships, and he always made time for people, especially his former players. And he always tried to be straight with them. He ran his football franchise like a family business – and his kindness and desire to please everyone in Cleveland wound up nearly costing him everything he’d ever worked for and toward with the NFL.

Modell relinquished control in 2004 with his family retaining a 1% stake in the team, but his presence within the Ravens organization was consistent and joyful. He was a regular visitor, watching practice in his traditional golf cart and dining in the cafeteria amongst the players, telling any number of his litany of sometimes corny, sometimes off-color, and somehow always entertaining stories.

Art loved to laugh.

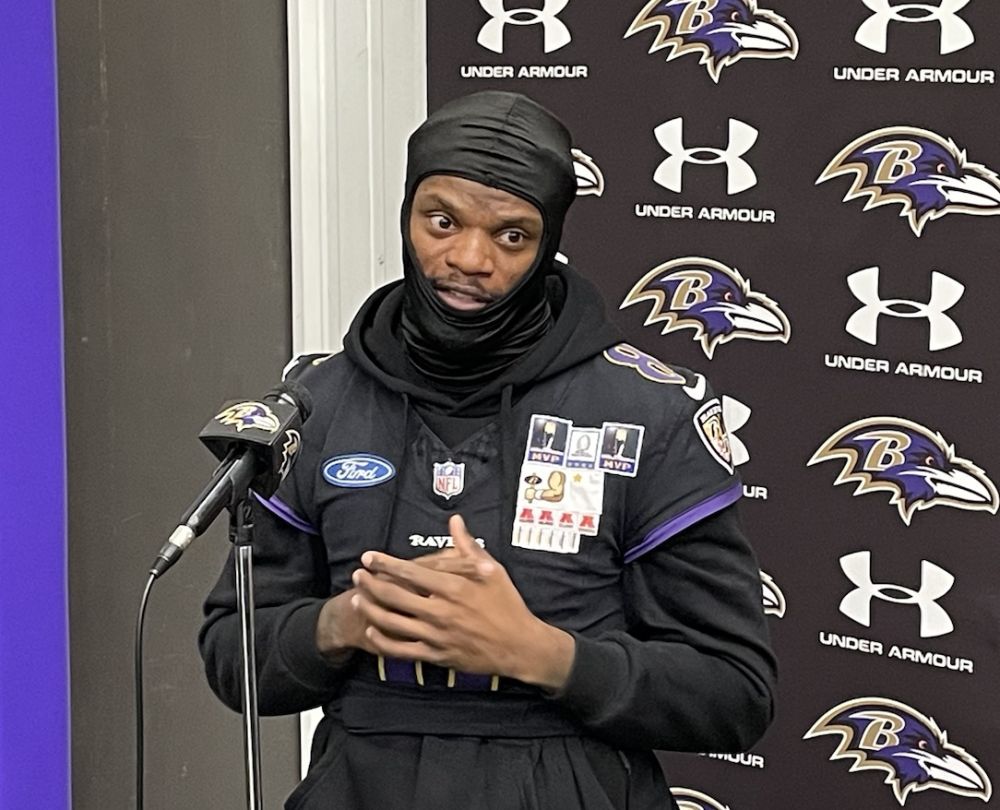

His relationship with Ray Lewis was more like father and son than owner and player. He drafted Lewis in 1996 and No. 52 was his star, the modern day lightning rod and Hall of Famer who brought a championship to Baltimore and who Modell flew to Atlanta and testified on behalf of during the summer of 2000.