For Reed, a trip home to New Orleans was indeed “two tickets to paradise,” the title of an old Eddie Money song that he repeatedly sang out of tune throughout the Ravens’ stretch run that wound up playing as part of a TV insurance ad in the middle of NFL games. Reed spent the week talking about everything from his contract status to his Hall of Fame worthiness to his time in New Orleans as a star prep athlete. He was extremely outspoken about his fines and the changing safety rules of the NFL – and his displeasure with the changing ethics of the game when tackling receivers. Reed used the Super Bowl forum as a chance to be heard as a veteran player who was headed to the Hall of Fame.

Lewis, who remembers his first Media Day in 2001 as part circus, part defense and part defiance, was back in the spotlight again. On that day in Tampa, he was 12 months removed from the Atlanta murders and only six months past the trial and fallout when the media pressed him repeatedly with the same questions until Shannon Sharpe walked over to his podium and lectured the group. As his Last Ride became more prominent, some media outlets came back once again to rehash that night in January 2000 in Buckhead. Quite frankly, it was expected.

But what he awakened to on this 2013 Media Day was unexpected.

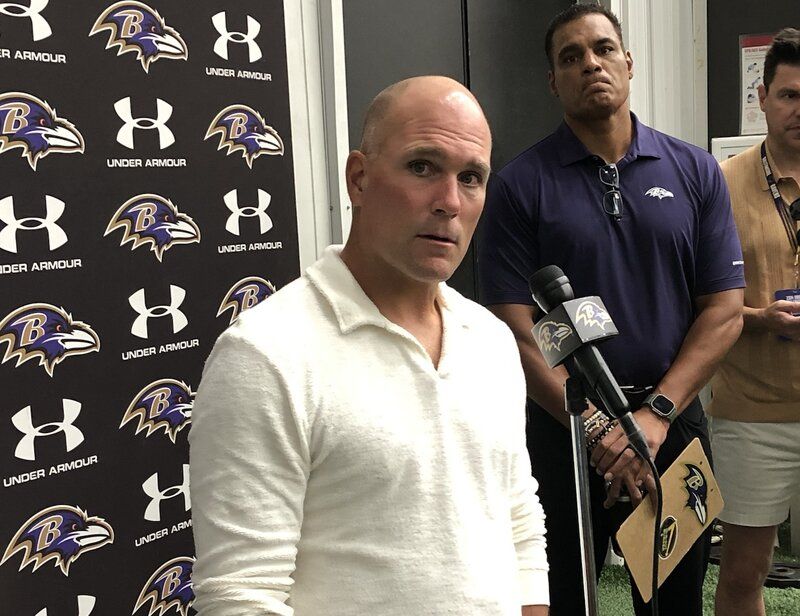

At 6:15 a.m. on Tuesday morning, the folks from Sports Illustrated issued a courtesy call to Ravens vice president Kevin Byrne and the media relations staff that they were publishing an expose on deer antler spray, which contains IGF-1, a substance banned by the NCAA and by every major pro league for being considered a performance-enhancing drug (PED). The story was released just minutes before the Ravens were to take the field at the Superdome for Media Day questioning. SI.com alleged that Lewis contacted a company in Alabama right after his right triceps tear looking to obtain this extract that could get him back on the field to compete in the playoffs.

They contacted Lewis, who seemingly shrugged it off and went about answering the questions and immediately discredited the report and repeated the same refrain each day in New Orleans. The furthest Lewis would go was to say he was agitated by the allegations and certainly the timing was a setup to claim a sleazy media victory for Sports Illustrated and for the “source” – a guy in a garage trying to sell his products as a miracle cure for athlete ailments.

“It’s so funny of a story, because I never, ever took what he says or whatever I was supposed to do. And it’s just sad, once again, that someone can have this much attention on a stage this big, where the dreams are really real,” Lewis said. “I don’t need it. My teammates don’t need it. The 49ers don’t need it. Nobody needs it.

“Don’t let people from the outside ever come in and try to disturb what’s on the inside,” he said he told his teammates. “I’m too blessed to be stressed so, nah, you’re not angry. You can use a different word. You can use the word ‘agitated,’ because I’m here to win the Super Bowl. I’m not here to entertain somebody that does not affect that one way or another. And for me and my teammates, I promise you, we have a strong group of men that we don’t bend too much, and we keep pushing forward. So it’s not a distraction at all for us.

“The trick of the devil is to kill, steal and destroy. That’s what he comes to do. He comes to distract you from everything you’re trying to do. There’s no man ever trained as hard as our team has trained. There’s no man that’s went through what we went through,” Lewis said. “So to give somebody credit that doesn’t deserve credit, that would be a slap in the face for everything we went through.”

The NFL already had some unique controversy and challenges with Super Bowl XLVII in New Orleans. It was the first time coming back to The Big Easy since Katrina, and the league had now made the Superdome its home 10 times for America’s biggest game. But when the game was awarded in May 2009, commissioner Roger Goodell couldn’t have known how unpopular he would soon become in New Orleans and throughout the entire region.

At the end of the 2011 season, Goodell found evidence that Saints players and coaches instituted an internal bounty system that paid bonuses for deliberately knocking out or injuring opposing players. Administered by defensive coordinator Gregg Williams and carried out by a multitude of personalities on the team, it had been going on for years. A stickler on integrity of the rules, Goodell handed out stiff fines, penalties and suspensions throughout the New Orleans organization. This included head coach Sean Payton, just two years removed from a Super Bowl title, being suspended for the 2012 season. The Saints finished 7-9, and many in Louisiana held Goodell responsible for a lost season when the team could’ve been hosting and playing in the game.

Instead, the hated 49ers were in The Crescent City. Beginning in 1970, San Francisco and New Orleans shared the same NFC West division and the Saints, while doormats for many for many years, were routinely the homecoming carcass for the Joe Montana-Steve Young era of the 49ers. Many in New Orleans considered the 49ers the archenemy because of three decades of whippings at the hands of San Francisco’s glory teams. Saints fans openly told Ravens fans all over the city to “beat the stinking 49ers.”