“Today I consider myself the luckiest man on the face of the earth. And I might have been given a bad break, but I’ve got an awful lot to live for…”

– Lou Gerhig (July 4th, 1939)

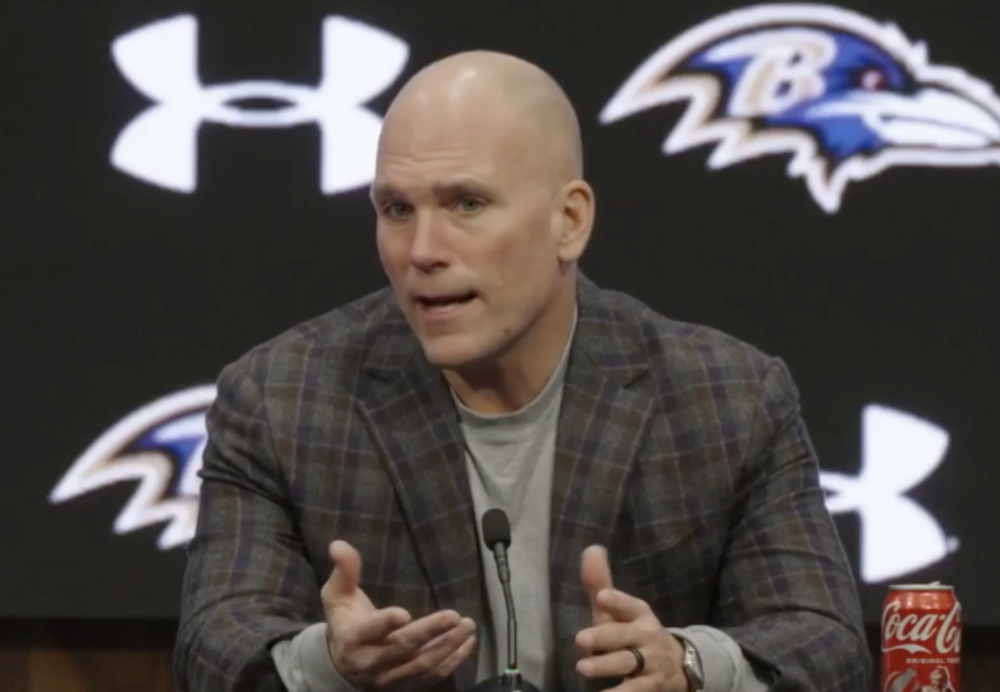

IF YOU VISIT THE BALTIMORE RAVENS’ facility in Owings Mills, it’s virtually impossible to miss the office of O.J. Brigance. His office door is always open, and it’s in the main foyer hallway, the most traveled area in the building for any employee or visitor. If you want to eat or go to the bathroom at the Under Armour Performance Center, he’s almost like a toll stop. You have to stop or at least slow down and acknowledge him.

It’s hard to know what the many young, incoming Ravens players or staff employees first think when they enter their new workplace and pass the office of Brigance, who sits in a very complex wheelchair-like device in front of a communication device called a Dynavox, which faces toward the door.

There are more than a handful of bonds that link the two Baltimore Ravens Super Bowl championship teams beyond Ray Lewis, but none more spiritual than the journey of O.J Brigance over the 12 years between confetti celebrations that demonstrate just how much lives can change, transform and, in some cases, deteriorate.

O.J. Brigance was No. 57 on the Super Bowl XXXV champions in 2001, the special teams captain who made the first tackle of the game on that beautiful night in Tampa. He was also the starting middle linebacker on the Baltimore Stallions Canadian Football League Grey Cup championship team of 1995. He’s the only man with a ring from both league’s championship teams from the same city.

And now, at 43, he sits motionless, all except for the flicker of his warm, bright eyes that allow him to communicate with the world around him via this amazing communication device that has kept his virtual world untouched despite his body betraying him, slowly disintegrating in front of everyone.

He gave his body to football all of his adult life. Now that same body, once a perfect physique honed by Brigance’s incredible drive, determination, and work ethic in the gym, has withered away. His spirit however remains transcendent for all who are in his presence.

He first felt the symptoms during a racquetball game in 2007 at the Ravens facility. From the time the franchise moved from Cleveland to Baltimore, beginning at the dumpy old facility on Owings Mills Boulevard about three miles away from the castle-like palace in the woods off Deer Park Road, the exhausting window wall game has been a staple for coaches, scouts, and various office personnel to blow off steam, get in a sweat and compete with each other for the “King of The Court” title. Racquetball, not cornhole, is the original, game of choice in Owings Mills. Brigance, a regular in the rotation in a building full of pretty fit athletes and former athletes, noticed some weakness in his right shoulder, his strength and range of motion were slowly changing so he sought out a neurologist. He was an athlete. He knew his body, and he knew something was wrong.

After a battery of tests, he and his wife Chanda were given the stunning diagnosis: O.J. had Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis.

A.L.S. is a motor neuron disease, first described in 1869 by the noted French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot. It occurs rarely and spontaneously. To date, except in strongly genetic forms of the disease, the cause of ALS is not completely understood. The last decade has brought a wealth of new scientific understanding, but how it starts in the body is still unclear.

Commonly known as Lou Gehrig’s disease and outside of the United States as Motor Neuron Disease (MND) or Charcot’s Disease, it is a progressive neurodegenerative disease that attacks motor neurons in the brain (upper motor neurons) and spinal cord (lower motor neurons) and affects muscle function. The motor neurons control the movement of various voluntary muscles, including the diaphragm. Associated with the loss of motor neurons to function in A.L.S., the various muscles cells waste away (atrophy), resulting in increased muscle weakness. A common first symptom is a painless weakness in a hand, arm, foot, or leg, which occurs in more than half of all cases. Other early symptoms include difficulty with speech or swallowing. In conjunction with these symptoms, an individual will have twitching and cramping of muscles (called fasciculation), stiffness in muscles (spasticity), increasing loss of motor control in hands, arms and legs, weakness and fatigue, slurred or thick speech and difficulty breathing or swallowing.

About 10 feet outside his office, in a long lighted hallway, the team pictures from all 17 squads of Baltimore Ravens players over the years adorn the walls. The 2000 Baltimore Ravens team photo features Brigance positioned right in front of Ray Lewis. Twelve years later, Lewis would play in Super Bowl XLVII that Brigance would watch from his wheel chair. Twelve years later, Brigance’s body is all but paralyzed and bound to a motor-operated device that allows him to communicate with anyone who has a few extra seconds of patience to allow him to use his eyeballs to connect phrases and words to create a unique conversation.

In a world of faux motivation and phony pep talks, the mere presence of Brigance has been an enduring, endearing, and daily point of motivation, strength, and courage for the entire Baltimore Ravens organization since his diagnosis in May 2008. And despite his illness, Brigance spends three hours getting ready each day to report to work four days a week.

New Ravens players are eager to learn the story of the man simply called Juice. If you’ve been with the team since 2008, you know the story and its impact on the team. Once the new arrivals see his office and the relationship he has with so many folks, they want to know as well. Who better to share an inspiring legend than Mufasa?

Joe Flacco and Ray Rice don’t ever remember him walking or speaking normally and they’ve been with the team five years. For anyone who arrived after 2008, they never saw O.J. Brigance walk, let alone fly around the field they way that they do every day at practice or on game days.

And once they hear his story – and see the pictures and videos — and there have been plenty of teammates beyond Lewis and other people in the building who can tell it because they’ve lived through it and witnessed every day. The new inductees are quickly reminded to never take a day for granted and never have a reason to complain.

Orienthal James Brigance, was born to teenage parents in Houston on September 29, 1969, the same year that another famous O.J. — Orenthal James Simpson – was the Heisman Trophy winner and No. 1 overall draft choice of the Buffalo Bills out of USC. Brigance attended Rice University and was a three-year starter, graduating in four years in 1991 with a degree in managerial studies with an economics concentration. The Owls were 9-34-1 during his time at Rice, including 0-11 in his sophomore year.

After being undrafted by the NFL, the Dallas Cowboys and head coach Jimmy Johnson gave him a quick look at a spring mini-camp in 1991, but he was just 6-feet tall and barely 220 pounds, extremely undersized for any NFL linebacking corps.

Brigance, undeterred and still following his dream of playing in the NFL, went to Vancouver to play for the B.C. Lions of the Canadian Football League. The CFL game, tailored for players of his size and speed, allowed him to immediately play, improve, and flourish. He barely made a living salary in Canada, but loved playing. He still believed he could play in the NFL one day and saw he was improving. He played three seasons with the Lions, and was an All-Conference linebacker.

In 1994, when Baltimore fetched a CFL team with an owner named Jim Speros, Brigance signed as a free agent to come to 33rd Street as a member of the Baltimore Stallions, who were initially calling themselves the “Colts” until the NFL and Bob Irsay issued a cease and desist order. Thousands of fans, hungry for local professional football, filled Memorial Stadium many nights in the summers of 1994 and 1995 to watch a team in blue and grey jerseys while studying the wacky CFL rulebook — complete with rouges, three-down possessions, 12-man sides and wider, 110-yard fields. Brigance was recruited to Baltimore by head coach Don Matthews, who had been a coach with the Saskatchewan Roughriders the previous season and knew that Brigance would be a difference maker for the new Stallions.

The roster rules of the CFL were that Canadian teams needed a minimum number of natives on their team,s but the teams in the United States – Baltimore, Birmingham, Memphis, Shreveport and San Antonio – didn’t have the same quota so the American teams were dominated with an outstanding crop of mostly speedy but undersized U.S college players whose bodies were more designed for the rules of the game.

Simply put, Brigance flourished. He was in many ways, the Ray Lewis of the Baltimore Stallions, running on the same Memorial Stadium field that No. 52 would roam beginning in September 1996. He was a dominating player for the Stallions and led them to a pair of Grey Cup games, which is the CFL’s Super Bowl.

“He was truly an ambassador for the CFL in Baltimore,” said Mike Gathagan, who was the Stallions media relations director in 1994-95, but who came from a television sports background at WMAR-TV. “We were a new team, and we needed a star, a guy who was good on the field and good in the locker room and good in the community.”

Brigance did every radio show, every newspaper interview, and every community event with kids, old Colts Corrals fan clubs, hospitals, schools – you name it. Brigance was bright, articulate, handsome and warmly embraced everywhere he went on behalf of the Stallions.

“He was really our ‘go-to’ guy for everything we did because he loved doing it, and he was just so good with people,” Gathagan said. “In 1995, our second season, when our schedule came out we were trying to sell tickets and get Baltimore excited about us during the summer that Cal Ripken was in the middle of The Streak, and we called him and he said, ‘Let’s tee it up and get out there.’ We went to every radio station and all four TV stations that day for live hits with O.J.”

Colts legend Tom Matte, a part owner of the Stallions, regaled Brigance in those days with stories about the Johnny Unitas and Bert Jones days. Remember: the Ravens didn’t exist in 1994, and Brigance found a Baltimore community that was awash in enthusiasm for football, but very anti-NFL after losing the Colts to Indianapolis in 1984. Matte called Brigance his “favorite player.”

“Our equipment manager once told O.J. that he led the league in complete sentences,” Gathagan said. “O.J. always had that ‘it’ factor. He was intelligent and articulate. He was a leader on the field, in the locker room, and just about everywhere he went.”

Brigance’s versatility in the CFL game allowed him to play rush end or middle linebacker, and Mathews assembled a team around him that was outstanding as the Stallions went to the Grey Cup championship game in both of their seasons in Baltimore – both led by the defense of Brigance’s units. In 1994, the home-standing B.C. Lions beat the Stallions in Vancouver, 26-23 in front of 55,097 at B.C. Place. In 1995, just 13 days after Art Modell announced his intentions to move the Cleveland Browns to Baltimore, the Stallions won the Grey Cup beating the Calgary Stampeders 37-20 in Regina, Saskatchewan on a day when wind chills were minus-20 degrees on the Canadian plains.

Brigance knew the Stallions were done, but later called it a “blessing from God.” He said he would’ve stayed in Baltimore and continued playing in the CFL and wouldn’t have tried to get an NFL job if the Stallions had remained in tact and Modell never moved the Browns to Maryland.

The enthusiasm for the Stallions carried over to the Ravens immediately, and 33rd Street was full of purple just nine months later when a kid named Ray Lewis came to town as the new middle linebacker. For Brigance and many like him, those seasons in the CFL allowed them to continue their football education and improvement after college in the hopes that some NFL scout would see them and give them a chance.

No NFL scout was going to fly to Vancouver, but many were within driving distance of Baltimore, and there was always a full row of them at every Stallions game at Memorial Stadium in Baltimore.

Seven former Stallions eventually played in the NFL — Brigance, Denver running back Mike Pringle, Miami guard Mark Dixon, Pittsburgh punter Josh Miller, Pittsburgh tackle Shar Pourdanesh, Green Bay long snapper Rob Davis, and Washington special-teamer Reggie Givens. Perhaps the best Stallions player of them all, Elfrid Payton, a 6-foot-1, 235-pound rush end went into the CFL Hall of Fame in 2010, but never played a down in the NFL. Pringle is also a CFL Hall of Famer.

Every once in a while you can spot a CFL pennant or an old ticket stub around Baltimore, but there’s still a fire burning somewhere for those Grey Cup teams of 1994-95. Every year in the fall, on his birthday, Brigance still gets a greeting card from an anonymous Baltimore sports fan who simply signs the card: “A Stallions Fan.”

By the winter of early 1996, Brigance had endured the end of the Stallions in Baltimore and after five years in the CFL wanted to see if the NFL was ready for him. The Browns, en route to Baltimore were looking for ways to sell tickets. They held a workout and Brigance, by his own admission, didn’t perform well.

Frustrated with his agent, he had a heart-to-heart with his wife Chanda, who challenged him to take control of his destiny. She told him to make the calls himself instead of relying on an agent. “Who could sell O.J. Brigance better than himself?” she reasoned.

Putting his pride and ego aside, Brigance got an NFL media black book with all of the team contacts and started with Arizona and Atlanta and went alphabetically through the league calling personnel people for a tryout. The calls always began with “My name is O.J. Brigance, and I’ve played five years in the NFL” and included “Can I send you a tape?” and “Can I come down and work out for you?”

He got two chances – one in Houston, his hometown where the Oilers were headed to Tennessee and a very lame duck, and the other in Miami, where head coach Jimmy Johnson remembered him from 1991 and loved that he’d been playing competitive football and thriving for five years. Brigance chose Miami because he thought he had the best shot of making the team there.

The Dolphins gave him uniform No. 45 at their steamy, hot training camp in late July 1996, and Brigance saw that as a sign that he wasn’t going to make the team because what linebacker would wear 45?

His biggest booster during that camp in Miami became special teams coach Mike Westhoff, who had been a part of the Baltimore Colts staff when Irsay brought the Mayflower vans to Owings Mills in March 1984. Westhoff saw Brigance’s speed, ability to shed blockers and find a ball carrier. He saw that O.J. was a hard worker and a film room guy. Along with another ham and egg special teamer Larry Izzo, Brigance made the team and thrived on the Dolphins’ third unit, becoming a two-time captain and a Pro Bowl alternate.

After injuries in 1998, he overcame back, elbow and ankle surgery to appear in all 16 regular-season and two playoff games in 1999. His Dolphins teammates named him their recipient of the Ed Block Courage Award. At the March 2000 banquet at Martin’s West, Brigance approached then-head coach Brian Billick and told him he’d love to come back to Baltimore, this time in an NFL uniform. Billick saw how warmly received Brigance was at the event and how the crowd remembered his contributions as a Stallions linebacker.

In June 2000, Ozzie Newsome signed Brigance, along with Dallas Cowboys special teams ace Billy Davis, to become a significant contributors on the Ravens’ special teams unit that would win Super Bowl XXXV just six months later.

The only touchdown the Ravens gave up at that Super Bowl in Tampa was when a special teams breakdown allowed Ron Dixon of the New York Giants to break a 97-yard kickoff return. That play always bothered Brigance because of what the shutout meant to Ray Lewis and the defense. Following the Ravens’ win, Brigance signed an above-market free agent deal to go to the St. Louis in 2001 and played in his second Super Bowl, coming an Adam Vinatieri field goal shy of a second ring.

Brigance appeared in one game as a member of Bill Belichick’s New England Patriots in 2002 and his playing career was over.

In early 2003, longtime running back Earnest Byner was leaving the Baltimore Ravens front office for a coaching job with the Washington Redskins. Byner, a favorite of Art Modell, was running the Ravens’ player development department. Byner was in Cleveland when Modell had instituted his “Inner Circle” program to help young players on the team deal with real-life issues off the field. So Byner, along with Ozzie Newsome, knew intimately what players could be going through outside of the building that would affect how they performed on Sundays.

“Player development doesn’t sound like a big assignment, but it was one of the more important jobs around,” said Billick. “Because of the intimacy with the players on sensitive topics – religion, women, agents, where to live, dealing with fame, how to save money — it almost has to be a former player, but it has to be the right player. And sometimes, the person in that role will find out stuff that a coach needs to know about what’s going on with a player’s life that can affect them. It’s a fine line, and there are only a few people who can do that kind of job.”

Brigance needed a job, and Billick had one to fill with Byner’s departure.

“O.J. was an absolute natural for it,” Billick said. “You felt great giving him the job because he was such a classy guy, such a perfect person for that role. And he was also a guy who had special affection for the 53rd guy on the team because he’d been that guy coming to a new city, to a new life. O.J. was an asset in that role.”

The same selfless role Brigance performed on special teams was the one he assumed in player development. In 2003 and 2004, young Ravens players who needed mentoring, advice, and assistance turned to Brigance, and he helped them with every aspect of their lives in Owings Mills. He even got involved on the television broadcasts on Rave TV, something he really enjoyed and worked hard on improving because of all of his experience all the way back to the Stallions, when he was the face of the franchise.

In 2005 and 2006, the Ravens and Brigance won the NFL’s “Best Player Development Program” award.

Then in 2007, there was that weakness in the shoulder on the racquetball court and Brigance’s life changed forever.

O.J. and Chanda were devastated when the diagnosis came. The prognosis, as in all A.L.S. cases, was grim, truly a death sentence knowing the use of your extremities will begin to deteriorate and eventually use of arms, legs, and the ability to talk will be gone.

The disease is insidious, fast-moving, and claims most of its victims within five years.

Brigance broke down, cried, pondered, and finally gathered himself. “God has prepared me,” he told himself. “I must find a way to help people.”

O.J. Brigance has always been a deeply religious man. You can Google any story about him from the 1990’s with the Stallions in Baltimore or the late 1990’s with the Miami Dolphins or back into Baltimore over the last 13 years and you’ll find nothing but references to God and his deep belief in Jesus Christ. He frequently referred to “the path of Lord” long before his diagnosis.

He thought that a kid from Rice playing in Vancouver in the CFL was a great way to earn a living. He loved his first trip into Baltimore. He fulfilled his lifetime dream of making it to the NFL in Miami, came back to Baltimore and won a Super Bowl. He came a field goal away from winning another in St. Louis the following year. And, all of it, he’d say many times was “God’s plan.” He always said the critics called him too small to play in the NFL, but “God had another plan for me.”

Well, this time, God did have another plan, and Brigance believed that plan was to help patients of A.L.S. while he was a patient, too.

The first person in Owings Mills that Brigance came to immediately following his diagnosis was head coach Brian Billick.

“The first day of training camp O.J. came to me and said he needed to talk,” Billick said. “We’re moving equipment around up in Westminster and the place is a mess and I knew it must’ve been important because he knew I didn’t have a lot of time. But he came into that little office at the hotel, almost nervous, and began talking about ‘other opportunities in life.’ He went on for 20 minutes about this new ‘huge opportunity’ and it sounded like he was trying to tell me that he was taking another job and leaving the Ravens because he was being vague.”

“Then, he drops this bomb on me: ‘Coach, I have been diagnosed with Lou Gerhig’s Disease.’ I was floored. By the time he had come to me, he already saw this as an opportunity to help other people. He framed his diagnosis up as an opportunity. That’s just the way O.J. is. He’s a special man.”

O.J. and Chanda’s faith that helped them find the strength to accept the diagnosis also led them to make the decision that the diagnosis would not define them. And while he was still capable, Brigance was going to structure a plan that would define his new mission in life – helping A.L.S. patients and their families cope with the same disease that stood to end his life and world prematurely.

“Through the triumphs, there has come a greater confidence, and through the challenges, has come a greater clarity of purpose” is one of the mission statements for the Brigance Brigade, a non-profit group founded by O.J. and Chanda in 2008 that helps patients and their families buy equipment and get the support needed for all of the unseen complications and expenses that A.L.S. brings.

“The platform that I’ve been given can give tremendous exposure to A.L.S. and an opportunity to do some good,” Brigance said. “When adversity strikes we often want to shrink back and go into our shell, and there’s a time to do that. But we also experience things so we have an opportunity to impact others.”

Working with the Robert Packard Center for ALS Research at Johns Hopkins, Brigance began using his Dynavox machine in 2010 to communicate with the world through his eyes powering this unique and quirky device that acts similarly to a smart phone with a voice activation where he speaks to everyone around him all day and writes to those who aren’t in his presence. And, again, he does all of this with his eyes!

He’s been speaking to the team regularly since 2008. He’s still like a big brother to Ray Lewis and Ed Reed. And the same joy, wisdom, and playful spirit he brought to the locker room as a player is now employed by Brigance using the Dynavox and it’s funky, computer-generated voice.

In 2008, when Brigance first got his wheelchair, Ravens running backs coach Wilbert Montgomery put up speed limit signs in the long hallways so Brigance would stop motoring past offices.

“If I can’t run fast anymore, I’m going to drive fast,” Brigance told The Los Angeles Times at the time. “We all recognize what the reality is. But we’re mature enough to recognize the possible and to have fun. People look at my diagnosis. But I look at other people’s circumstances. Every one of us endures some form of adversity in our life, but somehow we find the courage to get up and keep on living. Same game, different name. When people look at me and are encouraged by me … I look at children with ALS … Whenever I go to the doctor, I look around and say, ‘Man, I got it good. I have family that loves me and an organization behind me. I get to do what I love to do each and every day. There are some who can’t walk. Some can’t speak.’ We’re all dealing with our own adversity. But how we’re choosing to deal with it is key. All we can ask is, ‘How can we make life better?’ Even in the midst of adversity. It’s not about why. It’s about what can I do.”

Brigance still employs a wicked sense of humor. When you see him, your natural human compassion makes you feel sorry for him. Empathy is only the beginning. You want to give him a hug. You want to make sure you don’t cry yourself. You want to be upbeat because it’s obvious that he is upbeat. It’s almost impossible for it to not be awkward initially, but somehow he’ll throw some one-liner at you with the computer-generated voice that will bring you to your knees with laughter.

Brigance returns emails from players – and media members or folks in the Baltimore business community who write to him – usually within hours. He spends his whole day communicating with everyone who was in his world when he was not immobile.

“The toughest thing for people to understand about ALS is that I am still the same person and still have all my mental capacities. I can recognize you, so you don’t have to introduce yourself every time I see you. I just can’t talk or move. Oh, and I am not deaf. No need to scream. I can hear you just fine!”

But people still scream. And people still cry when they see him. It’s complex. It’s complex for those who have known Brigance from the first day he walked into the Ravens office coming from Miami. And for those who knew him as the community relations machine for the Baltimore Stallions in the 1990’s. Or anyone who was a teammate or sought his counsel as a player development ear once he took an office job in Owings Mills.

He is always classy, always spiritual, and always spoke of God. He is always strong, outgoing in his faith, and convivial — the kind of person any NFL team would want representing their brand in the community. O.J. Brigance — the player — was a gem. Fighting this illness, he has become an institution in the Ravens organization and a living, breathing testament to daily courage.

“He’s my greatest motivation,” Lewis said. “He’s the example of the way a man should live, regardless of where you find yourself. He’s my hero.”

Brigance leans on a favorite Bible verse from II Corinthians for understanding the symbiotic nature of his past and his present: “My grace is sufficient for you, for my strength is made perfect in weakness.”

“The toughest part of living with ALS has been not being able to work out and be active,” Brigance told the CBS crew before Super Bowl XLVII. “Instead of getting depressed about it, I decided to praise God for the abilities I do have and keep it moving. The message I try to deliver to the players is that life will never turn out to be fair in our eyes. We must make the most of the life God gave us. Life is about being humbled through triumphs and attentive during challenges. We grow and gain greater clarity in life if we have vision to see beyond the tears.”

Billick said that it’s natural for football players to respond to people who are having difficulty.

“Every player has been injured and knows what pain is, what struggle is all about,” Billick said. “Every player had to struggle to get to the NFL because it’s not easy. And no matter their circumstance or road, they’ve all witnessed O.J. in Baltimore over the last six years and think ‘that could be me.’ Most are aware that by the grace of God that they are as a fortunate as they are because they pass O.J.’s office on the way into the locker room.”

“We’re always telling players that this game ends for everyone and don’t think that the money or the ability will last forever. O.J. is there daily, reminding all of us how tenuous it all is and to seize the day, seize the moment.”

Steve Bisciotti and the Baltimore Ravens have been very good to O.J. Brigance and have stuck by his side at every turn. His medical expenses are enormous. The amount of help and nursing he needs daily to get to work is monumental. Several of the 2012 Ravens, including Brendon Ayanbadejo and Ray Rice, were extremely close to O.J., visiting his office on a daily basis. There are a lot of people in that building who truly love him.

Head coach John Harbaugh made his feelings and intentions known right away in 2008. His first order of business was carting his entire roster off to downtown Baltimore on buses, making them run in O.J. Brigance’s inaugural 5K through the streets of the city as part of a warm up for practice. It was a team-building event. It was his first act, aligning with a player that Ray Lewis had played in the Super Bowl with and every person in the building on the business side had almost a decade of relationship with in Owings Mills.

To Harbaugh, it is always about faith and family.

“It’s bigger than wins and losses; this is about being men, about growing,” Harbaugh said. “That’s something we’ve learned in a very real way by watching O.J. in this because he’s the strongest man in the building. It’s not even close. And you know that once you get to know him, he’s pure strength.

“Like the Bible says, ‘Our strength is made perfect in our greatest weakness,’ And here is O. J., visibly in a weakened physical state, yet in an incredibly strong spiritual and intellectual place, and he shows that every day. He’s just a shining light in the building, and we all definitely are energized by that.”

Rice called him “a guardian angel.”

With sports, sometimes you’ll see P.R. stories of motivation on a pre-game special or NFL Films piece. There’s something dramatic or motivational in every NFL locker room. For the Ravens, the situation with O.J. Brigance has been a true source of motivation for years. It’s in your face, and it’s heartbreaking, uplifting, emotional, and has become part of the fabric of the team.

Brigance is courage, personified. And in an organization full of men who share his religious beliefs and faith in God, he truly believes “a man with an outstanding attitude makes the most of it while he gets the worst of it.”

During the Ravens’ run to the Super Bowl in January 2013, Brigance’s story and the Brigance Brigade got universal coverage after Ray Lewis’ “Last Dance” day in a victory over the Colts when he honored a guy everyone on the team simply calls, “Juice.”

“One of the great men I’ve ever met in my life: O.J. Brigance,” Lewis said to his teammates in the locker room as he held the game ball. “Me and this man, we hosted something that this team is chasing again. We once held the Lombardi Trophy for this city. We held it. This man has taught me — don’t ever complain in life! Don’t ever waste time in life, either. You want to go get something done? Go get it done. He’s the role model. He’s the example of what it means to be facing crucial circumstances and, because of your mind set you can live through anything and do whatever you want to do.”

Two weeks later, Brigance participated in the coin flip before the AFC Championship Game in New England and spoke to the victorious team in the locker room just before they hoisted the Lamar Hunt Trophy in the locker room.

“Congratulations to the Baltimore Ravens,” Brigance said through his Dynavox. “Your resiliency has outlasted your adversity. You are the AFC champions. You are my Mighty Men. With God, all things are possible.”

In Cincinnati, Bengals coach Marvin Lewis watched the AFC Championship Game postgame speech by Ray Lewis. “It was incredible. That sent chills down your spine and tears to your eyes. This guy, what he was as a player, when he came to the NFL and how hard he worked and seeing Ray and the whole organization honor him, wow. I can remember telling [linebackers coach] Jack Del Rio in 2000, ‘What a great set of linebackers you have, how lucky you are to have those guys, the quality of those people as men.’ ”

Brigance’s father Marcus told a Houston television station during Super Bowl week: “The Ravens organization and the players are willing him to live.”

“Super Bowl XLVII means so much to me, not because of the game,” Brigance said in New Orleans. “It’s the journey it took to get there. The journey is where personal growth and maturation comes. I know the stories of the men on this team. They have all overcome challenges and adversities to be on this national stage. It makes me extremely proud for them.”

Amidst this dark diagnosis and the six years of rapid, torturous loss of his bodily functions, Brigance still believes in a cure. “Why can’t I be the first one healed from it?” he has said many times.

“I would describe the last five years living with ALS as revealing,” he said before the Super Bowl. “Revealing of who I really am as a husband, son and a friend. I was patient, but could also be stubborn and self-reliant. Over the past five years as my physical abilities have diminished, I have realized what special people I have around me. They have become my hands and feet. Beginning with my wife, my family, my nurses, and friends. I have very special people in my life. I have seen love in action, and that is a blessing!”

“My belief in Jesus Christ has given me the strength to face every day with purpose and passion. I was created specifically to make an impact on families of people with A.L.S.”

As Chanda once said: “Prayer is not a part of our life. Prayer is our life!”

“Every moment he’s awake he’s trying to help people’s lives and will until he meets his maker,” said Gathagan, who has known him longer than anyone in Baltimore. “He’s the best human being I’ve ever met. Period. It’s an honor to know him and to have known him all of these years.”