The Ravens have provided no shortage of exciting players in more than two decades in Baltimore.

Some local fans would describe the pre-game dance of Ray Lewis, the greatest player in team history and face of the franchise, as something resembling a religious experience. A pair of Pro Bowl running backs, Jamal Lewis and Ray Rice, were legitimate threats to score every time they touched the ball. Two All-Pro return specialists — Jermaine Lewis and Jacoby Jones — shined on the most critical stage the NFL has to offer. Many others have brought thrills for an organization with two Super Bowl championships in its trophy case.

But none quite compare to nine-time Pro Bowl safety Ed Reed, who was officially elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame on Saturday. The first-ballot selection was perhaps the most anticlimactic achievement in a career that made observers anticipate the most unexpected of feats.

Fellow first-ballot Hall of Famers Lewis and Jonathan Ogden are the greatest players in team history on their respective sides of the ball, but the ball-hawking Reed is the most exciting we’ve witnessed. Unlike running backs, wide receivers, or kick returners who regularly touch the ball when in the game, Reed would seemingly come out of nowhere, even after the opposing coaching staff would preach all week about not letting him do it.

The sight of Reed with the ball brought emotions ranging from euphoria as he’d turn the game’s outcome with an unlikely touchdown to occasional horror as he’d inexplicably lateral the ball in traffic, sometimes giving it right back to the opposition. Reed unquestionably moved to the beat of his own drum, but you couldn’t ask more of an entertainer and play-maker over 11 seasons in Baltimore.

The simplest objective of the safety position is to prevent an opponent from wrecking the game with an explosive pass play, but there was nothing “safe” about the way Reed stalked in the secondary, creating nightmares for quarterbacks and often doing the very thing the opponent was trying to accomplish against the Baltimore defense — score. When arguably the greatest quarterback in NFL history felt compelled to put “Find 20 on every play” on his wristband, what else really needed to be said about his case for Canton?

Reed’s 64 regular-season interceptions rank seventh on the NFL’s career list while he’s the all-time leader in interception return yards. No player has more postseason interceptions (tied with three others with nine), and Reed became the first man in league history to score return touchdowns off an interception, a fumble, a punt, and a blocked punt. He set the NFL record with a last-second 106-yard interception return for a touchdown to seal a tight game against Cleveland in 2004 before breaking that mark four years later with a 107-yard interception return to put away a win against Philadelphia.

In all, 46 passers were intercepted by Reed in his career with half of that group going to at least one Pro Bowl and six being the starting quarterback of a Super Bowl winner.

Though Reed was named the NFL Defensive Player of the Year in 2004, the greatest of his individual achievements came late in the 2008 season when he registered an extraordinary 10 interceptions over a seven-game stretch that culminated with two — one returned for a touchdown — in a playoff victory at Miami. For context, the entire Baltimore defense from this past season had only 12 in 17 games.

The 2002 first-round pick from Miami is tied for 19th on the Ravens’ all-time touchdowns list (13) despite having the football in his hands far fewer times than anyone else — all offensive players — in that top 20. The number of actual planned times Reed touched the ball was even lower as he registered a modest 30 punt returns in his career and never caught a pass or recorded a rushing attempt as an offensive player.

Not only one of the greatest safeties to ever play the game, Reed had an extraordinary ability to block punts before coaches eventually kept him out of potential harm’s way in his later years. The 5-foot-11, 205-pound Reed blocked four punts over the first 27 games of his career and frequently drew holding flags as opponents tried to account for his explosive jump off the line of scrimmage.

So often praised for his football instincts, Reed’s preparation was exceptional as he followed Lewis’ initial lead when it came to watching film and studying the playbook. That enabled Reed to so often be in the right place at the right time as he knew where the ball was going before the quarterback even threw it. Later in his career, he passed on those study habits to younger teammates, quietly exhibiting strong leadership in the shadows of Lewis’ camera-friendly methods.

Even his closest confidants acknowledged Reed’s personality ran hot or cold with the position of the hood of his sweatshirt often signaling whether you could engage in spirited conversation or should probably steer clear that day. He could ruffle feathers with comments about even his own teammates, but his intentions usually came from a good place. And while dealing with injuries late in his career, the veteran safety would both ponder retirement and campaign for a new contract in the same breath.

That was Reed.

A nerve impingement suffered late in the 2007 season zapped him of the underrated physicality he displayed early in his career and left him with neck and shoulder pain, but he played through it and did so at the highest level, making five more Pro Bowls while picking his spots to deliver the occasional hit. Even while sporting a red jersey to signal no contact during practices, the veteran safety would light up an unsuspecting young wide receiver from time to time, again reflecting that eccentric personality.

Super Bowl XLVII is most remembered as the culmination of Joe Flacco’s historic 2012 playoff run and Lewis’ last ride, but it was the night Reed finally raised the Vince Lombardi Trophy after years of playing with offenses that couldn’t hold up their end of the bargain. It would be Reed’s final game in a Baltimore uniform — he’d play one more season split between Houston and the New York Jets — but Ravens fans shared in his joy a couple days later as he bellowed out the words to Eddie Money’s “Two Tickets to Paradise” at the victory parade.

It was one last thrill in a career that was long before destined for a gold jacket and the football paradise that is Canton.

No Raven brought same excitement as newest Hall of Famer Ed Reed

Luke Jones

Luke Jones is the Ravens and Orioles beat reporter for WNST BaltimorePositive.com and is a PFWA member. His mind is consumed with useless sports knowledge, pro wrestling promos, and movie quotes, but he often forgets where he put his phone. Luke's favorite sports memories include being one of the thousands of kids who waited for Cal Ripken's autograph after Orioles games in the summer of 1995, attending the Super Bowl XXXV victory parade with his dad in the pouring rain, and watching the Terps advance to the Final Four at the Carrier Dome in 2002. Follow him on social media @BaltimoreLuke or email him at Luke@wnst.net.

Podcast Audio Vault

Share the Post:

Right Now in Baltimore

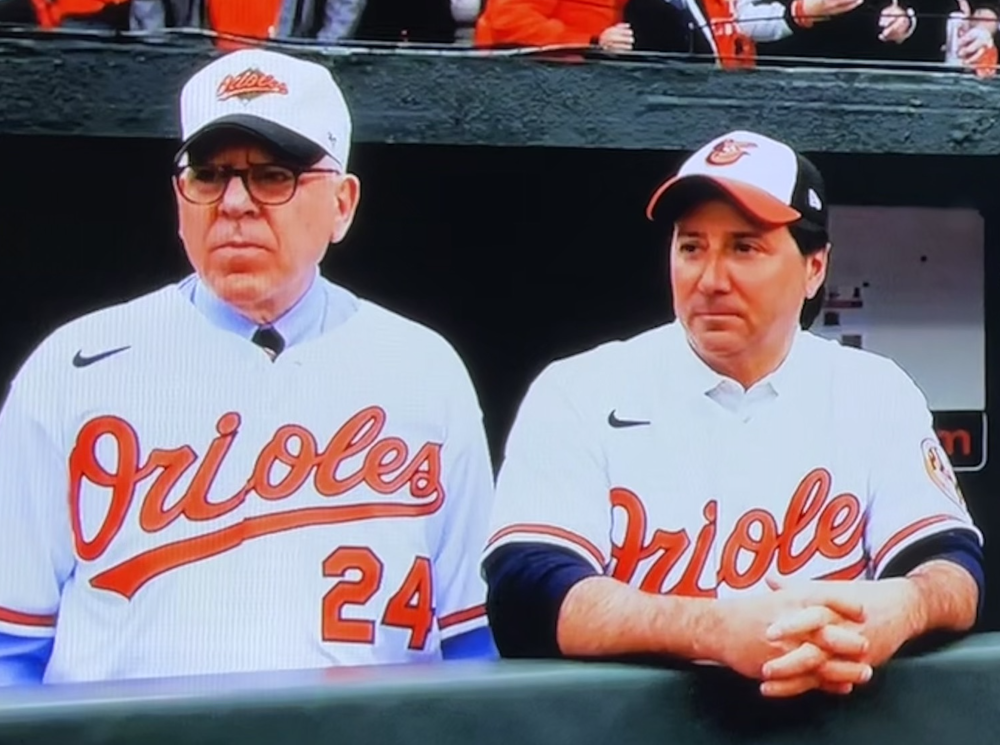

As MLB moves toward inevitable labor war, where do Orioles fit into the battle?

We're all excited about the possibilities of the 2026 MLB season but the clouds of labor war are percolating even in spring training. Luke Jones and Nestor discuss the complicated complications of six decades of Major League Baseball labor history and the bubbling situation for a salary cap. And what will the role of the new Baltimore Orioles ownership be in the looming dogfight?

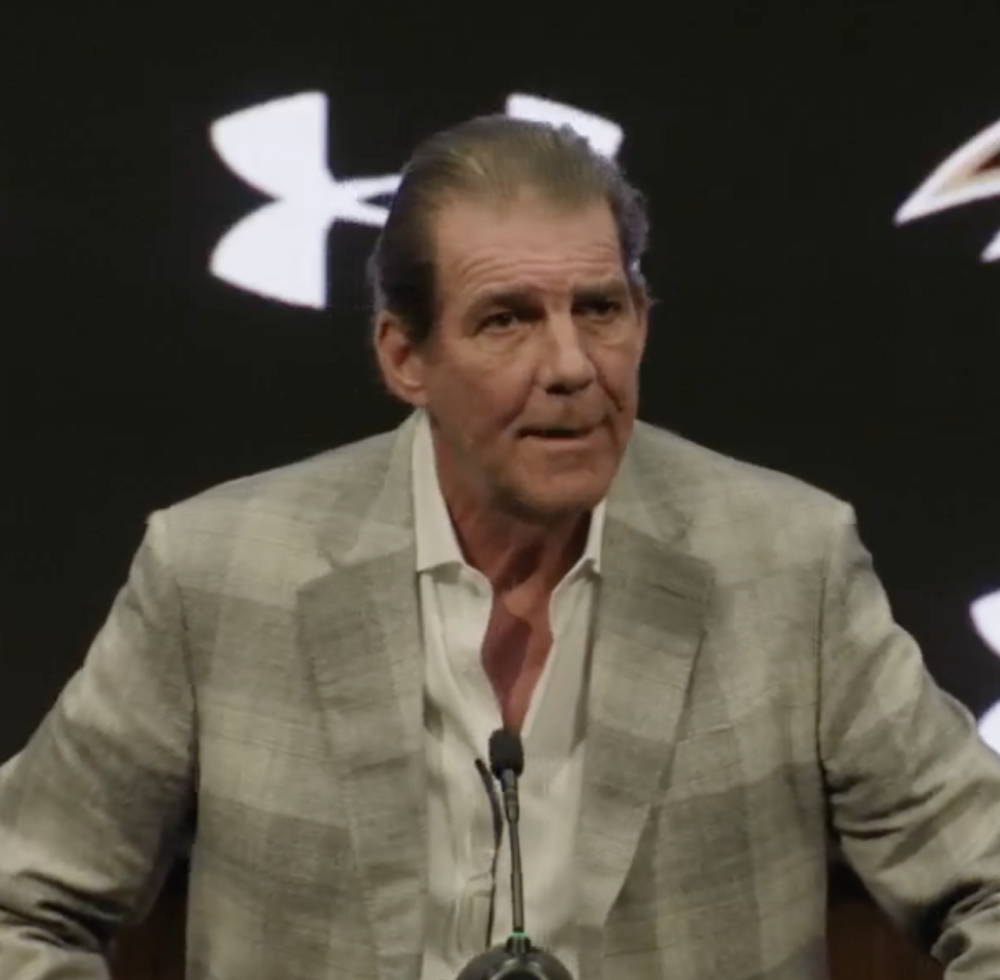

Profits are up, accountability is down and internal report cards are a no-no for guys like Steve

The NFL continues to rule the sports world even in the slowest of times. Luke Jones and Nestor discuss the NFLPA report cards on franchises and transparency and accountability amongst billionaires who can't even get an Epstein List regular who just hired John Harbaugh to come to light and off their ownership ledgers. We'd ask Steve Bisciotti about it, but of course he's evaporated again for a while...

Orioles' Westburg out through at least April with partially torn elbow ligament

Since playing in the 2024 All-Star Game, Jordan Westburg has endured a relentless run of injuries.