“We didn’t force anybody to get into this process …No one was forced to continue at any point anymore than anyone is forced to bid for the Olympics or forced to bid for a plant in an area. So, that’s a judgment people have to make. Maybe they prefer to have a museum in their town or a plant. It’s their judgment. It’s not for me to make judgments about what communities want to do with their resources and their people.”

– NFL commissioner Paul Tagliabue to WMAR-TV, at the Rosemont Hyatt in Chicago, Ill., in October 1993, in a message to Baltimore’s NFL fans about what they could do after the city had just lost its only hope for an expansion team to Charlotte and Jacksonville

SOMETIMES WORDS JUST CAN’T EXPRESS or convey the true emotion of an event.

For those of you lucky enough to be from Baltimore and have a stake in Charm City’s professional football team – a real stake, an indescribable emotional bond – you know the feeling that I have as I stroke these keys.

To say that any true Baltimore Ravens fan or supporter would be in complete and utter disbelief about the events that transpired between Nov. 6, 1995 and Jan. 30, 2001, would be an understatement.

The Baltimore Ravens, of the National Football League, defeated the New York Football Giants at Raymond James Stadium in Tampa, Fla., on Jan. 28, 2001 to bring the Vince Lombardi Trophy back to Baltimore for the first time since 1971. Just a little more than five years earlier, the city not only didn’t have a team, but there was truly no hope among the populace of ever getting an NFL team back to the town where the Baltimore Colts were pilfered in the middle of a snowy night in March 1984.

The score that night in Tampa, a decidedly lopsided 34-7 blistering of the NFC champs, will be forever etched in NFL lore. More than 130 million people all around the world watched as Ray Lewis and Brian Billick hoisted the glittery, silver Lombardi Trophy toward the Florida sky on a beautiful evening as confetti flew through the air. The NFL Films video of the accomplishment will play longer than any of us live, for millions more to see and enjoy.

Yet I have the distinct feeling that if you truly care as much as I do, there’s still a resounding feeling of complete disbelief.

I was there. I was there from the very beginning. I fired the first question to then-Cleveland Browns owner Arthur B. Modell when he hit the stage in parking lot D of Baltimore’s Camden Yards complex to announce his intentions to move his team east. I was the first person from Baltimore to shake the massive hand of Jonathan Ogden in New York City on April 20, 1996, when he became the first true member of the Baltimore Ravens. Less than five months later, I brought future Hall of Famer Ray Lewis his first crab cake, during a live radio broadcast after the Ravens’ first victory over the Oakland Raiders. I was the first person from Baltimore to greet future head coach Brian Billick as he walked through a depressing and dismal locker room in Minneapolis on Jan. 17, 1999 after just losing his first chance to go the Super Bowl as the offensive coordinator of the Minnesota Vikings. And there I was again, aloft my adopted 50-yard line seat, just behind the Giants bench in Tampa, where I watched through streaming tears of joy as NFL commissioner Paul Tagliabue grudgingly presented Modell and his Baltimore Ravens the league championship trophy.

I was there for just about everything. I’ve watched the tape, over and over again. Brandon Stokley beating Jason Sehorn to the end zone. Duane Starks streaking toward the end zone after picking off a Kerry Collins pass. Jamal Lewis powering into the end zone. I’ve seen them all a thousand times by now.

And you know what?

I still can’t believe it.

Say it out loud with me. The Baltimore Ravens won the Super Bowl. The Baltimore Ravens won the Super Bowl. The Baltimore Ravens are the football champs of the world.

For those who subscribe to the theory that revenge is a dish best served chilled, this is a story for you. A story sadly missed by the more than 3,000 media members who covered Super Bowl XXXV in Tampa that night. A story missed by virtually everyone outside of the tiny cluster of fans who truly understand and appreciate the scope and depth of the accomplishment.

In one 60-minute football game, Baltimore and its fans got even with just about everyone who ever got in the way or tried so desperately to keep the NFL and a championship out of Charm City.

The list of people, cities and entities that had it stuck to them – and had it coming in a big way – both living and deceased, would bring a smile to anyone who ever appreciated the high tops of Johnny Unitas or popped open an icy-cold National Bohemian Beer (that’s Natty Boh to the locals) in the land of pleasant living on the shores of the Chesapeake Bay.

The city of Baltimore had its Old Bay and crab-stained mitts around the Lombardi Trophy and there wasn’t a damned thing anyone could do about it.

Robert Irsay, the original Satan, who stole the beloved Baltimore Colts off to Indianapolis on a snowy night in 1984, might have lined his pockets temporarily with some cash from the move to the Hoosier Dome. However, not only does his franchise seem perpetually cursed since the move, playing in just five playoff games in 17 seasons, but Baltimore now had possession of the trophy he died having never laid a greedy finger on – nor has his offspring, Jimmy.

Jack Kent Cooke, the eccentric longtime owner of the Washington Redskins, who tried so hard to put his NFL team in Laurel, Md., nearly a decade before, would not only have his family cut out of the football business after his death, but his wish to marry the Baltimore and Washington markets to his football team never came to fruition. The Baltimore Ravens were not only birthed against Cooke’s wishes, but they beat his beloved Redskins into the winner’s circle. Even his successor, Daniel Snyder, who tried unsuccessfully to pry Baltimoreans away from the Ravens during the summer of 2000 with a silly advertising campaign, was forced to eat some Raven crow.

Then there were the other owners in the league, who conspired for a dozen years to keep Baltimore out of the NFL, while enjoying big, fat crab cakes during the expansion derby of the early 1990s.

Bill Bidwill flirted with Baltimore for several weeks in 1986, making a brief statement about Charm City’s charms during a Harborplace stop for the media. He then moved his St. Louis Cardinals to Arizona with the promise of a new stadium and a wave of support from the community. Thirteen years later, that stadium is still a blueprint and his family is still searching for its second playoff victory. His team was also one of the Ravens’ late victims in an 11-game winning streak that culminated in the presentation of the Lombardi Trophy.

Malcolm Glazer, an outsider who was very active in the doomed Baltimore expansion bid of 1993, wooing politicians and citizens alike, bought the Tampa Bay Buccaneers two years later and went on to backhand Baltimore during a press conference in Florida by saying that he’d “much rather own a team in Tampa than in Baltimore.” Not only did his team not make it to their hometown Super Bowl at Raymond James Stadium on that night in January 2001 after outbidding the Ravens for wide receiver Keyshawn Johnson in a high-profile preseason trade with the New York Jets, but Glazer and his sons, Joel and Bryan, sat helplessly in the club level as Baltimore was presented with the Lombardi Trophy on the very field that their family had built. As a cruel footnote from the football gods, the Glazer family was also forced to watch as Trent Dilfer, the one-time franchise quarterback and savior whom the Bucs had rudely sent into exile just nine months earlier, waved the Lombardi Trophy toward his former employers and the town that turned on him.

Charlotte and Jacksonville were the lucky recipients of the expansion derby of 1993. Carolina Panthers owner Jerry Richardson, who had many ties to Baltimore as a former Colts player, and Jacksonville Jaguars owner Wayne Weaver, the shoe king who rallied a third-world American city into the NFL, surely had made their own football fun with their newfound fortune in the Sun Belt.

Both teams made it to their respective league championship games in just their second season in the league in 1996, both battering the Ravens in their inaugural year in Baltimore. The Jaguars actually knocked on the door again, just three years later hosting the AFC Championship Game, which they lost to the upstart Tennessee Titans.

Both still had beautiful stadiums and strong fan support six years later. Prior to the 2000 season, the Jaguars had been a one-franchise pariah to the Modell family, crushing the Ravens/Browns 10 consecutive times over five years.

Both Richardson and Weaver, universally disliked by Baltimoreans for the cities that they represent and the way that Baltimore was disregarded and disrespected by the league in 1993, might still one day touch the Lombardi Trophy. But it will only be after it has been sitting in Baltimore for 52 weeks.

Abusing the city of New York might be the biggest and storied accomplishment of all. Baltimore had long displayed the “second city” inferiority complex to the Big Apple. I spent my entire childhood hearing my Dad lecture me about the lopsided New York-Baltimore history. The Knicks beat the Baltimore Bullets in the NBA numerous times. The Miracle Mets dispatched of the Baltimore Orioles in “amazing” fashion in 1969. Nine months earlier, Joe Namath followed up his poolside guarantee of a victory as the lowly AFL champion New York Jets embarrassed the Baltimore Colts and the NFL with a 16-7 victory after entering the game an 18-point underdog.

Since then, the Lombardi Trophy had visited the Big Apple twice with the Giants, the Stanley Cup seven times with the Islanders, Devils and Rangers, and the baseball championship seven times with the Mets and Yankees. Any self-respecting Baltimorean can recount the events of Oct. 9, 1996 with amazing precision, the night that Jeffrey Maier grabbed an apparent fly out from the glove of Orioles outfielder Tony Tarasco, leading the Yankees to victory and an eventual world championship that kept Baltimore sports fans at bay once again.

It was only a rivalry in the mind of my Dad and other Baltimoreans. Folks in New York couldn’t find Baltimore with a sports compass. There were other victims of greater significance, like the Red Sox and the Cowboys, in Gotham City.

Year after year, Baltimoreans had to read and see and hear about New York and its great sports teams and great sports fans and great sports traditions. Once Peter Angelos began running the beloved Baltimore Orioles into the ground with an endless series of bumbling transactions, there was almost no hope for Baltimore fans to finally one-up New York.

The Ravens’ victory that night not only brought a championship back to Baltimore for the first time since the Orioles won in 1983, but it in turn denied New York and its arrogant fan base another taste of a championship. No small task, I assure you.

In one 60-minute flurry of vicious defense and pounding offense, Brian Billick’s Baltimore Ravens put the ultimate screws to everyone who had ever stepped in the path of Baltimore’s inevitable resurrection to glory.

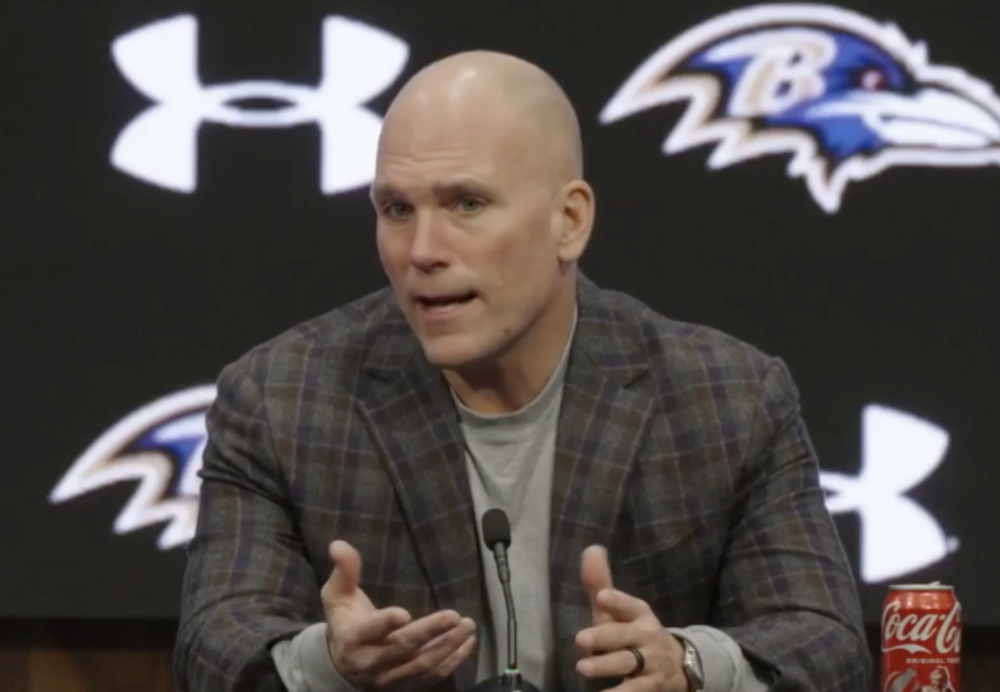

And the coup de grace – the eating of the cake or the pounding of sand, if you will — the one-man Baltimore hate machine himself, commissioner Paul Tagliabue, the Sun King, stood front and center before the entire world on CBS (and a cacophony of rousing boos also heard worldwide from the few thousand Baltimore fans who had seats at Super Bowl XXXV) and presented his Lombardi Trophy to the proud city he so publicly spurned so many times and the owner who embarrassed him by pulling the Browns out of the NFL’s beloved Cleveland.

“Art and David (Modell),” Tagliabue began, “the Ravens defense performed at a superb, record-setting level all season. They continued that performance through the playoffs, culminating with today’s very, very decisive victory over a strong Giants team. We congratulate you and we congratulate all of your players and Coach Billick and his staff and your whole organization for bringing this Super Bowl championship back to Baltimore and to Baltimore’s great fans for the first time in three decades. Congratulations!”

Paybacks, Mr. Commissioner, are a bitch.