The spat between Hall of Famer and TNT analyst Charles Barkley and Houston Rockets general manager Daryl Morey is just the latest example in the battle continuing to be fought across multiple sports.

The “old school” way of thinking versus statistical analysis.

Never mind that the mindsets aren’t mutually exclusive, you better choose one or the other in this fight!

Despite being a self-proclaimed baseball nerd — we’ll use that sport for our example — I’ve always maintained it’s up to the individual to decide how dedicated and in depth he or she wants to be as a fan. After all, we’re talking about sports and not matters of national security.

It’s supposed to be fun.

Embracing sabermetrics to adapt how I study the game in recent years hasn’t swayed my enjoyment in watching a perfectly-executed relay or a game-tying home run in the bottom of the eighth inning. Finding new ways to educate yourself about the game isn’t a mandate — however, it should be for those who work in the game and want to remain relevant — but it’s silly to criticize simply because we may not understand or be interested.

Admittedly, statistical analysis is heavy as it can quickly start to feel like a calculus lesson instead of a baseball discussion. With many of these advanced stats — OPS-plus, FIP, UZR, and WAR just to name a few — I’ve developed a functional understanding of what they mean and how to apply them without wasting brainpower remembering how to calculate them. It’s akin to enjoying the steak without dwelling on how it’s prepared at the butcher shop.

For anyone not convinced of the value of sabermetrics — but will at least humor me — I typically present three questions:

1. Would you rather have a .300 hitter or a .260 hitter?

Many — not all — traditional fans will go with the .300 hitter, which has long been viewed as a benchmark for greatness, but how much does batting average really tell us?

In this case, the .300 hitter could also be a free swinger who doesn’t walk often and hits for very little power. In contrast, let’s pretend the .260 hitter clubbed 60 extra-base hits and walked 80 times over the course of the season. Under such a scenario, the .260 hitter is likely to be the far superior option without getting into their value on the bases or in the field.

This is why on-base plus slugging percentage (OPS) is embraced while batting average is being thrown aside by many statheads as a limited piece of information. If you want to take it a step further, OPS-plus takes into account how a hitter’s home ballpark — think of a pitcher’s park in Oakland compared to a hitter’s park — impacted his performance and allows for better comparison among players across the league.

2. Do you want a pitcher with a 3.70 ERA last year or one who had a 4.00 mark?

Again, many purists will point to the hurler with the lower ERA and be right in most cases, but is it always that simple?

What about the defense he played with in comparison to the group that was behind the other pitcher? What if one was really lucky or had great misfortune over a number of starts?

Fielding Independent Pitching (FIP) is complicated to calculate, but it uses the outcomes a pitcher solely controls (strikeouts, walks, hit by pitch, and home runs) to produce a value on the same scale as ERA. Its intent is to eliminate factors such as defense and bloop hits in trying to assess a pitcher’s effectiveness and to help predict his future performance.

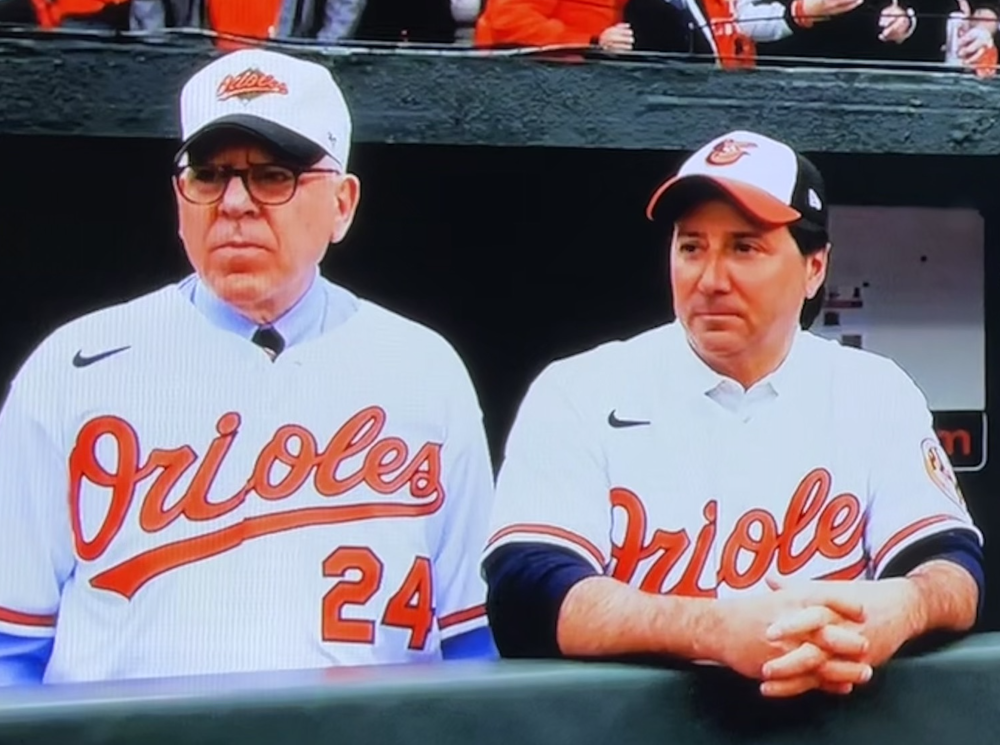

As an example, the 2014 Orioles ranked seventh in the majors in team ERA (3.44), but they ranked 24th in team FIP (3.96). It reflects just how much Orioles pitching benefited from the exceptional defense behind it — which confirms what many purists witnessed with their own eyes, mind you — and how it would likely fare with an average defense.

3. Would you prefer the shortstop who made six errors or the one who made 12 last season?

This question is a good one as baseball fans have long been prisoners to a lack of data to truly assess defense. Hypothetically, a player could stand in one spot on the field all year and not commit an error, but that would make him quite poor defensively, wouldn’t it?

Sabermetrics are ever evolving when it comes to measuring defense, but numbers such as Ultimate Zone Rating (UZR) are finally accounting for how much ground a player covers in the field. The measures aren’t perfect as there is fluctuation from year to year, but we’ve taken giant leaps from the days of simply quoting the number of errors, putouts, and assists a player collects.

To answer the above question, we need to know how the first player’s range compares to the second shortstop. If the latter gets to many more balls in the hole and up the middle, it’s logical to conclude he’s likely to commit more errors, but how many more outs will he also have created in the process?

Of course, the three above questions only scratch the surface of what’s out there in baseball.

Statistical analysis is about accounting for variables and answering questions. There isn’t one fancy statistic that should be viewed as gospel — or a number to which you become a “prisoner” in Orioles manager Buck Showalter’s words — in the same way that no person’s gut feeling or eyeball test is foolproof, either. Computers and numbers don’t play the games on the field, but they can tell us more about what’s happening and what is likely to happen next.

It’s possible to appreciate the human element as well as what the numbers say. In fact, we might even find that a statistic will confirm a gut feeling or an observation.

If more statheads were willing to explain their rationale and more traditionalists were open to learning, we wouldn’t have the embarrassing exchanges like we saw this week between an NBA general manager and one of the great players in league history.

There’s a place for both statistical analysis and traditional evaluation if we’re willing to embrace both.

And you don’t have to be a rocket scientist or a Hall of Famer to do it.