4. The Dumb Dumb error begins in Baltimore

“I don’t think any boss, anybody in charge should ever criticize subordinates publicly. That is even in this business here that Frank Sliwka operates [at The Barn in Carney]. If he has a problem with one of the employees I think he should take them in the back room quietly and tell should tell him or her what he objects to. I don’t think anyone should publicly chastise an employee. When you’re a boss you keep that kind of thing to yourself. And that’s what I said to Davey Johnson. And I’ll repeat it again and I’ve told him that since then. He’s a great manager. He’s a great guy. I love him like a brother and we get along fine. Except I’ve said to him, “If you have to criticize someone, you take him in your office, shut the door and let it be between you and the player.”

– Peter G. Angelos on WWLG Budweiser Sports Forum

March 1997

THERE COULD BE NO ENCORE for an act and a night as emotionally charged as the Cal Ripken 2131 night at Camden Yards in September 1995. Once again, there was no postseason baseball in Baltimore for the 12th consecutive year and Angelos, aided by the immortal Iron Man streak and the intense, family-like local passion for baseball, had enough revenue coming into the franchise to afford any baseball player he wanted in the marketplace. The club was swimming in money vs. its MLB foes. Plus, given his pro-player stance in the contentious labor dispute, many believed the Orioles would be a haven for free agents who wanted to sign with an owner who saw their side and wanted to win and put the best team on the field.

Looking ahead to the 1996 season, Peter G. Angelos was obsessed with one thing: bringing a World Series to Orioles fans.

Immediately following the 1995 campaign, Angelos fired manager Phil Regan and “accepted the resignation” of Roland Hemond, who was actually forced out, along with Frank Robinson, who was glad to leave the Orioles at that point and wound up working for commissioner Bud Selig in the MLB office.

Angelos was clearly running every aspect of the Baltimore Orioles at this point and was quite brazen in the media regarding his daily involvement. He bragged that he had enough time to run a law firm that was netting more than $15 million per year in personal income for him at the time and a MLB team on the side. Now with all of the “baseball people” gone except for his self-appointed farm director Syd Thrift, Angelos needed a new manager and a new general manager. He had already developed quite a reputation in the insulated, incestuous world of baseball men and lifers. He had owned the team for less than 24 months and had already pissed off every one of his 27 MLB partners, upstaged Cal Ripken on the biggest night of his life on national television and chased off two managers and a total of five baseball men: Roland Hemond, Frank Robinson, Doug Melvin, Johnny Oates and Phil Regan. Together they spanned three generations of baseball and touched virtually everyone in the industry with their true stories of an owner who called a manager into his office and demanded – among other things – which third basemen would be in the lineup on any given night.

A year earlier Davey Johnson, a former Orioles second baseman and World Series champion as manager of the 1986 New York Mets, was interviewed by Angelos and his internal committee that included Joe Foss and team lawyer Russell Smouse, but they instead selected Phil Regan, who they thought would be a hot commodity the previous year and whom never was given much of a chance under Angelos.

Johnson, who had a storied reputation for being snarky, cunning and anti-authority, took a shot at Angelos 12 months earlier when he didn’t get the job: “I heard they wanted an experienced manager and a proven winner. That’s why I interviewed for the job. But I guess that’s not what they wanted, right?” he told the media when he was clearly disappointed that he wasn’t selected in October 1994.

Now, after a disastrous year on the field in 1995 under Regan, Johnson’s name surfaced again and Angelos wasted no time in complementing the decorated yet difficult managerial prospect stating, “His baseball knowledge is impressive, and his strong background with the Orioles came through.” Johnson, meanwhile backtracked from any contentiousness in an effort to get the job: “I enjoyed meeting Peter,” he said. “You read stories about the Big Bad Wolf, but he was really nice.”

On October 30, 1995, Johnson was named manager of the Baltimore Orioles, the club’s third skipper in just 18 months under the Angelos regime. “This is a move in the direction of producing a winner,” Angelos said. “We are committed to building a winner in Baltimore, and Davey is a vital part of that effort. He has a winning attitude. He’s a very down-to-earth, forthright baseball professional with an extensive knowledge, and his record clearly establishes that.”

Was Johnson still sore about being passed over the previous year? “I do have a lot of pride, but I don’t have a big ego,” Johnson said. “Maybe I was hoping they’d offer the job so I could say no, but I discarded that idea in about two seconds because Baltimore represents my baseball roots. I thought it was a good fit a year ago, and I still do.”

Angelos allowed Syd Thrift to represent the Orioles at the MLB meetings in Arizona while he remained in Baltimore to interview a bevy of candidates to be the next general manager. Kevin Malone, a former Montreal Expos general manager, and Joe Klein, who had local roots and had been the GM of the Detroit Tigers, were considered to be the front runners but much like with every baseball decision made by Angelos, time wasn’t considered a pressing concern.

And despite most legitimate general managers wanting the opportunity to hire a field manager, Angelos did it backwards. The new manager, Davey Johnson was sent off to the MLB winter meetings along the farm director, Syd Thrift. Both were encouraged by Peter Angelos to recruit an appropriate general manager and working partner that would bring the Baltimore Orioles a World Series title.

In Phoenix, Johnson tracked down former Toronto general manager Pat Gillick, who was his old minor league teammate from Elmira in 1963, and tried to talk him into coming to Baltimore as the general manager of the Orioles.

Gillick left the Blue Jays at the end of the 1994 strike season and was headlong into trying to purchase the California Angels with Bill DeWitt Jr., who was originally the man who was to purchase the Orioles from Eli Jacobs three years earlier. But Disney’s massive money wound up finding owners Gene and Jackie Autry, so Gillick found himself out of the sport and wanting to get back into the right situation after building a legacy of greatness north of the border in Toronto.

Gillick engineered the complete dismantling of a losing expansion franchise and built the mighty Blue Jays, who had been hapless for their first decade of existence and a perennial contender once he had acquired the right talent to go along with a farm system that always found key players. Using the money that Skydome’s opening generated in 1989, Gillick got the Jays to the World Series three times and won a pair of World Championships, in 1992 and 1993.

He had been in baseball his whole life, scouting and running teams from 1964 until 1994. And now a year out of baseball, Gillick was itching for the action and wanted back into MLB but only in a capacity where he felt he could win.

The Baltimore Orioles had a lot to offer one of the best baseball minds in the world. A strong core of players like Rafael Palmeiro, Cal Ripken, Brady Anderson, Mike Mussina and Scott Erickson not to mention a treasure trove of the money that Camden Yards was printing and local hero-wannabe owner Peter Angelos was dying to spend.

Angelos, through the 1994 strike war, found himself at odds with every owner in the sport but he had developed a particular disdain for George Steinbrenner and the New York Yankees, who not only was far more famous – if not infamous – but “The Boss” also had re-emerged from his MLB exile with a vengeance and wanted to win again.

Gillick knew Angelos would spend on the best players but he wasn’t sold on his character or integrity after hearing the “street” reports about the meddling that the noveau riche owner in Baltimore had been doing from the outset. Gillick had also spent time with DeWitt, who was still freshly stung that he invested nearly $10 million in Team Angelos with Larry Lucchino in 1993 as a “partner” only to be completely marginalized after the purchase.

“I never thought [Angelos] had a game plan,” Gillick later told The Los Angeles Times. “I didn’t think he knew what he was doing.” Gillick also admitted to the newspaper that he was “disenchanted by the way Angelos left manager Phil Regan and general manager Roland Hemond hanging while talking to and about possible replacements.”

And the whole notion that a manager was looking to hire a general manager was an absurd model for success in any business. “I felt they had definitely put the cart before the horse,” Gillick said.

Meanwhile Davey Johnson sold Gillick profusely about the opportunity to win – and win quickly – if he came to the Orioles. As for Angelos? “I told Pat that Peter’s heart is as big as gold,” Johnson later told the newspaper.

Johnson, who signed a three-year, $2.25 million deal with the Orioles, convinced Gillick to come to Baltimore, where he signed a three-year, $2.4 million deal and they decided to go arm-in-arm back to the organization where they met as kids. “I never made it to Memorial Stadium, except as a spectator,” Gillick said of his career on November 28, 1995 when he took the job. “But it sure will be great to be a part of Camden Yards. What really convinced me to come back is that this club is close to winning.”

Angelos, who began his tradition of not attending major press conferences, released a “statement from the managing partner”:

“With Pat Gillick joining Davey Johnson, we now have the more formidable baseball operations team in the game,” he bragged. “Pat will oversee all aspects of the baseball operations. His abilities and leadership should provide Orioles fans with the championship they so richly deserve.”

With a myriad of top players on the market and an almost open checkbook competing in a depressed industry after the 1994 work stoppage, Gillick wasted no time in rolling up his sleeves and working his Rolodex. On December 14, relief pitcher Randy Myers was signed to a 2-year, $6.5 million deal. On December 20, Gillick signed B.J. Surhoff to a 3-year, $5 million contract and the next day added future Hall of Famer Roberto Alomar on a 3-year, $17 million deal. Alomar, considered one of the premier players in the sport, was a key part of the championships they won together in Toronto earlier in the decade.

When he failed to sign pitcher David Cone, Gillick later traded for lefties David Wells and Kent Mercker and the 1996 Baltimore Orioles were loaded with a $48 million payroll and ready to win a championship. Kevin Brown, Ben McDonald, Leo Gomez, Bret Barberie and Doug Jones were all dumped from the 1995 team, freeing up nearly $12 million in payroll for Gillick to spend.

Incidentally, in the three weeks between the hiring of Davey Johnson and Pat Gillick, the newspapers and media in Baltimore were being drawn by an even-bigger story unfolding in Baltimore.

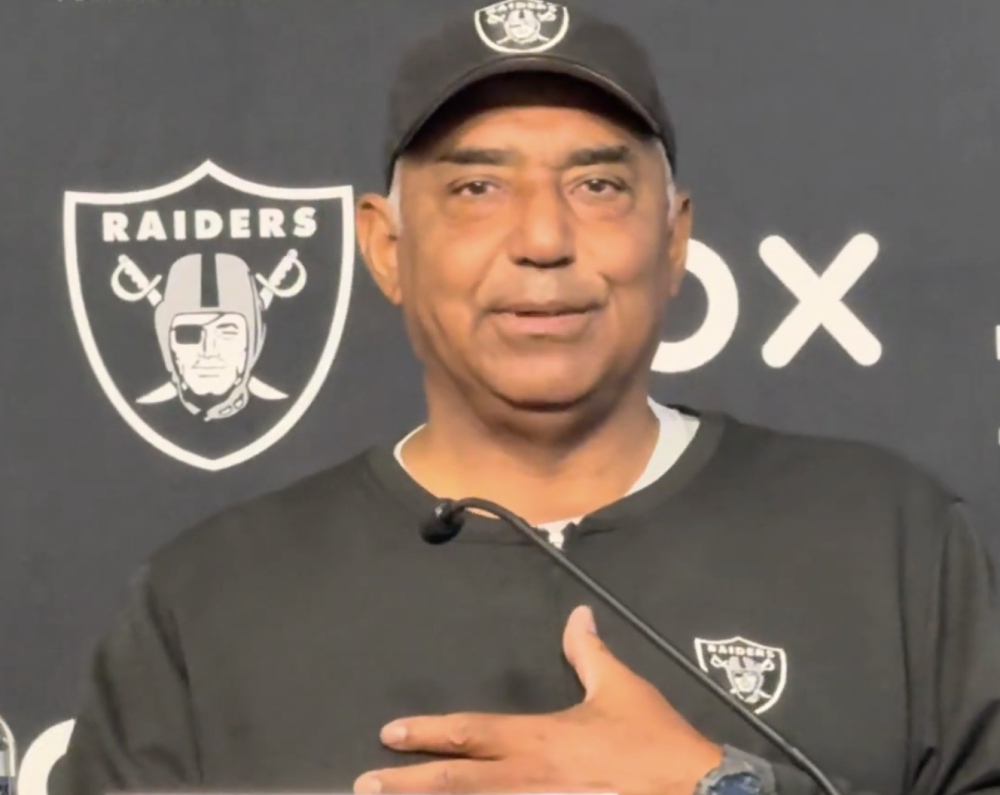

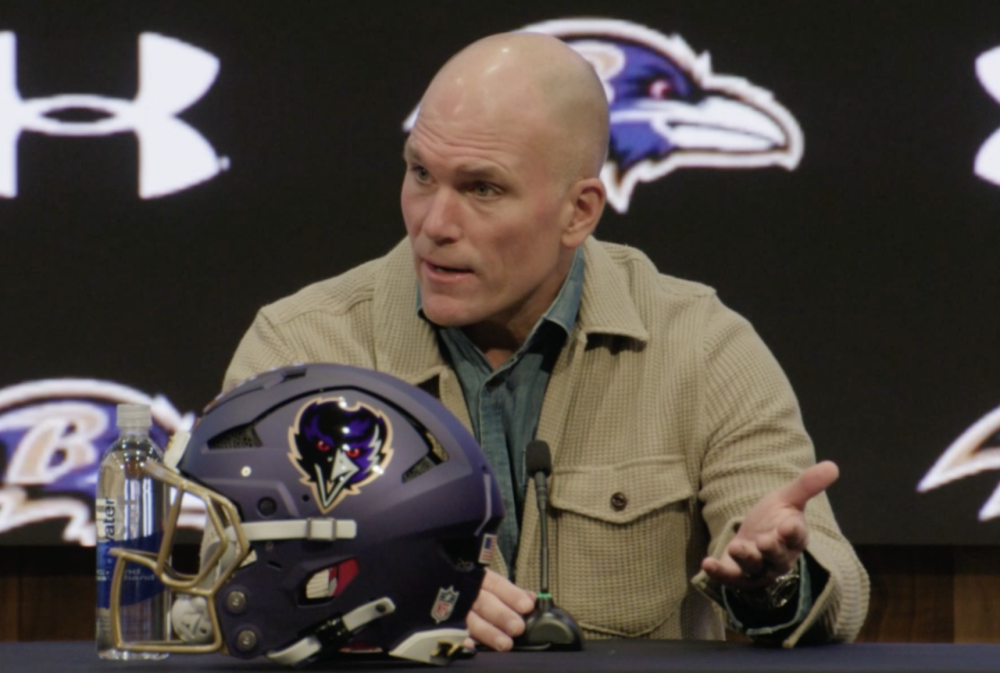

On November 6, 1995, Arthur B. Modell showed up in Parking Lot D to announce he was moving the Cleveland Browns to Baltimore for the 1996 season.

Peter Angelos had lost out on his chance to become an NFL owner in Baltimore.

In January 1996, the Baltimore Ravens were born.

***

BY EARLY 1996, THE PUBLIC personality of Peter G. Angelos was beginning to evolve and not all of the tales were pretty. The local newspapers – both The Baltimore Sun and The Washington Post covered the team as extensively as they covered local government – often referred to him as “King Peter,” because many employees (and the growing list of disgruntled, trampled ex-employees) were weaving tales of his unorthodox philosophies, actions and deeds.

When the Cleveland Browns franchise landed in Baltimore as the Ravens, their new human resources department was flooded with resumes from employees of the Orioles who wanted out of The Warehouse and away from the Angelos administration. For the players, knowing the Orioles owner wanted to win was more than enough and his checks cashed. For the management team, it was clearly a challenge given the many early departures in his tenure and the stories of meddling that were being reported in the media – and later blasted by Angelos with full character attacks faxed over to the bosses.

But the stories were all verified and true. The latest evidence began to mount on January 2, 1996 when Home Team Sports notified long-time broadcaster and former Orioles outfield John Lowenstein he would not be returning for his 12th year in the broadcast booth after a stellar career as a member of the 1979 and 1983 World Series teams. “Brother Lo,” as he was affectionately referred known by the fans and teammates, was left stunned and searching for answers.

“I have run the full gamut of emotions here from kind of stunned and shocked silence to bitterness and anger,” Lowenstein told The Baltimore Sun. “And I’ll tell you what: This move leaves me very distraught. This is very, very difficult to stomach, especially when you know you’re doing a good job. I was devoted to this job.”

Eschewing any routine professional courtesy, the move was made so late in the season – most baseball teams tell their broadcasters in October whether they’ll be returning the following season – that the irreverent Lowenstein wouldn’t have a chance to get another job in MLB. “I just wish I had been told about this early,” he told the newspaper. “Even if you’re told about it early, you can carry the ball for yourself, and maybe you can do some things for yourself.”

Former Orioles star pitcher Mike Flanagan had ingratiated himself with the Angelos family and once his legendary status as a player had come to an end, he was offered the job of color commentator for 1996 by Angelos. “I don’t know what more I could have done,” said Lowenstein, who would often offer honest and sometimes critical commentary about the games as they were unfolding.

“You have to be credible to your audience, don’t you?” he rhetorically asked the newspaper reporter. “And if that requires being a little critical, so be it. But there’s no way I was overly critical. I strongly supported this club in its mission to build a championship team. That’s why I admired [owner] Peter’s [Angelos] efforts. For this to come down like this was inexplicable.”

Nowhere in the story by The Sun does it mention the words “Peter Angelos.” The firing was attributed to Home Team Sports but it was very clear to everyone around the team what had happened with Lowenstein. But it was the first of many signs of changing times for Orioles broadcasts and broadcasters and the way the fans would be presented the “new era” of Orioles baseball on television, radio and in the media aftermath by the Angelos regime.

The 1996 Orioles made their new spring training home in Fort Lauderdale. The previous years had been a disjointed mess left over from the Eli Jacobs era. The Birds trained in Miami for 31 years and left in 1990 only to find Sarasota and St. Petersburg untenable. Many teams were getting bigger and better deals from sleepy Florida and Arizona retirement communities for publicly funded stadiums that could be used for minor-league facilities in great weather year-around. Angelos believed that the Orioles would be next in line to take advantage of a sweetheart deal in the sun for a spring home.

This dumpy facility in Fort Lauderdale that the Orioles claimed only became vacant after 1995 when the New York Yankees left it in a dilapidated state and it clearly hadn’t been renovated in more than 20 years. The Yankees vacated the stadium to move to a state-of-the-art facility in Tampa, which was owner George Steinbrenner’s adopted hometown. (He was originally from Cleveland).

And even if the Fort Lauderdale locker room was stocked with star players pulling up in $100,000 automobiles and the room boasted the highest payroll in the sport, no one on the 1996 Baltimore Orioles would be spoiled by the excess or lavish facilities during these six weeks of camp hell in the Florida sunshine.

The main stadium was located off I-95 in an industrial park that featured a commuter airport full of commercial jets whisking wealthy executives into what looked – and sounded – like deep left field. Planes were constantly motoring along and landing and taking off over centerfield. No one could feel good about this dump but Angelos and his very involved sons, John and Louis, chose Fort Lauderdale over the opportunity to share a Disney-sponsored facility that was being planned and built to spec near Orlando in the middle of the state. The Atlanta Braves had quickly taken the deal and would’ve been the Orioles partner in the project but Angelos didn’t like the idea of sharing the facility and he thought he should be making more money than the 1994 Disney deal afforded. Besides, Angelos and the boys also liked the fact that a private plane from BWI would allow them to literally land adjacent to the field to the watch Orioles games in March. It was door-to-door service plus Fort Lauderdale afforded a spicy nightlife, quick transfers to South Beach, a world-class horse racing track at Gulfstream Park and access to everything on the I-95 corridor and beach coast.

It was perfect for everything – except building a baseball team.

There were a myriad of “baseball” problems with the mere concept of hosting spring training in Fort Lauderdale. First, most teams had left the busy east coast of Florida over the years for the other side of the state. Plus, every road trip included a two-to-three hour bus ride to play games, even B games to get more innings for younger farm players. The stadium, built in 1962 by the Broward County government, had no gym, no area for lifting weights, no real amenities at all. Players who were making $6 million per year were expected to lift weights in a tent in the parking lot and eat lunch at their locker in a slummy, rundown clubhouse for six weeks. But the biggest issue was the lack of space for a minor-league facility to house all of the players and coaches in the organization in one complex. The Orioles maintained another dumpy facility for minor league players in Sarasota at Twin Lakes Park, which didn’t have a stadium to play games but had rudimentary baseball facilities and fields. The two sites were 203 miles apart.

For coaches, scouts and players who were on the bubble, it was a nightmare driving back and forth across what is known to locals as “Alligator Alley” in a rental car. It was literally the worst spring training situation in Major League Baseball and there wasn’t a close second place.

And Peter Angelos and his sons chose Fort Lauderdale over a brand-new, Disney-built park and complex with 10 other teams playing within a two-hour bus ride for better road game travel in Florida. Spring training is pretty rough on most franchises. It looks like a lot of golf and fishing for some but for talent evaluators, coaches and a player who isn’t a star and is desperately trying to be one, it’s just not conducive to winning. The split situation made everything harder for every person who wore a uniform in the franchise.

New manager Davey Johnson, a veteran of all of the wars, got the team ready to head north with a wave of new confidence and a team chock full of superstars. The Orioles won the first four games of the season and jumped out to an 11-3 start but quickly began to sputter. The team fell out of first place on April 27 and limped through the spring and into June, heading toward the All Star break barely teetering on relevance in the race. By July 28, the team was actually a game under .500 at 51-52 and looking like a bloated roster of All Stars who didn’t mesh. Gillick had traded for aging Orioles legend Eddie Murray on July 21, which delighted the fan base and Angelos, but not as much as winning some games would’ve helped in the heat of the summer.

The biggest single day on a general manager’s calendar is July 31 – the annual trading deadline. It’s the final chance to obtain playoff-eligible players without being encumbered by the waiver wave. It’s a day to evaluate your franchise’s intentions and decide whether you’re going to be a buyer or a seller for that year. Of course with Gillick, the question was “Stand Pat” or “Trader Pat”?

For the seasoned Gillick, whose 32 years of MLB experience taught him to look to the future, it was clear that the 1996 Baltimore Orioles were not a legitimate factor to be a playoff team and certainly not a World Series threat. Despite commissioner Bud Selig forcing an extra wild card team and a new division into Major League Baseball in 1995, vastly increasing every team’s chances of earning a postseason berth, Gillick felt that it was time to sell or trade off some expensive players for cheaper, younger, future talent. If it’s all a big gamble in dealing baseball players, this was a time to fold at the poker table.

Besides, Gillick had been on the phone for weeks prior, doing his job, poking at the marketplace through his vast resources of people and information, looking for takers for his star players and their huge salaries and he felt he could get good value in the deals he discussed with his contemporaries across the sport and free up payroll to be used in 1997 to reload. Both Gillick and Johnson signed three-year deals so they felt they had time to build a winner. As urgent as winning was for both men, they were of the mindset that this team wasn’t close enough.

Neither man thought the 1996 roster was working so they were looking ahead to making 1997 better.

In the days leading up the trading deadline, Gillick had been attempting to deal pitcher David Wells to the Seattle Mariners for a few prospects led by catcher Chris Widger. Rival general managers said that Gillick would couch many positions in the talks with a standard line: “I don’t think he’ll approve that,” meaning he would need the authority of Angelos to make any deal.

Gillick was finding it very hard to be in the baseball business and to be disempowered to make a move in the baseball department. It wasn’t the way he conducted business in Toronto, where he had the authority to do whatever was necessary. He and Angelos had discussed control issues eight months earlier when he took the job in November 1995. Gillick’s initial reservations and gut instincts about taking the job in Baltimore were coming back in sick, vivid reality. Angelos, on the day he convinced the decorated GM to come aboard, publicly said Gillick “would have all the leeway a GM should have, and maybe more.”

Now, on August 1, 1996, Bobby Bonilla and David Wells were still members of the Orioles and Gillick was despondent and angry about the situation. The narrative of the previous weeks became public in The Baltimore Sun as reported by Buster Olney:

In late June, the Indians and Orioles discussed a five-player deal that included Eddie Murray and Bobby Bonilla. Gillick, according to league sources, was ready to make the deal. Angelos said no, feeling the team could not win without Bonilla and the Indians were ready to dump Murray for almost nothing.

In the week leading up to the trade deadline, league sources say Gillick was prepared to deal pitcher David Wells to Seattle for three minor-league prospects, a deal that would’ve effectively ended the Orioles’ slim chances of contending for the wild card. Angelos said no, noting the Orioles’ obligation to fans who bought tickets expecting to see a contender.

In the final two days before the deadline, sources say Gillick arranged a four-player trade with Cleveland: Wells and Jeffrey Hammonds to the Indians for outfielder Jeromy Burnitz and young left-hander Alan Embree (who was on the disabled list). Angelos said no; again, trading Wells would’ve ended any hope of the Orioles contending.

The Orioles talked at length about swapping Bonilla to the Reds for a group of youngsters, the most prominent of whom was Triple-A outfielder Steve Gibralter. Like the other deals pursued by Gillick and assistant GM Kevin Malone, this trade would’ve given the Orioles at least one Triple-A prospect, the type of prospects the Orioles were lacking. Angelos didn’t want Gillick to shop Bonilla for a player who couldn’t help them immediately.

“To discuss dismantling the club in those circumstances is something ownership must be involved with,” Angelos said. “That’s not just a baseball decision. That’s an organizational policy decision.”

The Orioles were 53-52 and five games back in the AL wild card race on July 31. They were 12-29 vs. teams with winning records. The bullpen, decimated by injuries to Armando Benitez, Roger McDowell and Arthur Rhodes, had been atrocious. And the fans in Baltimore were furious with the effort and heart the team was showing in front of sold-out crowds every night and the high expectations that come with the highest payroll in the sport and a 12-year playoff drought.

It was the fans and their loyalty that Angelos brought into question with the notion of trading current MLB players for future prospects. Of course, the Baltimore Ravens were in training camp for the first time and would be playing NFL games at Memorial Stadium in September. Angelos had no intentions of allowing his baseball team to be an also-ran in the first month that Art Modell’s carpet-bagged team would be spreading its purple wings across the Chesapeake Bay region. If Angelos saw George Steinbrenner as the enemy in his own sport, clearly Modell and his pirated football team became the enemy in his backyard. The Ravens had also raided some key business employees from The Warehouse as well over their first eight months in business in Baltimore, people who were eager to depart the Angelos monarchy. And on the sponsorship side, the NFL was now calling upon local businesses and former Orioles salesmen were the ones making the calls to familiar local executives to spend money with the new purple birds.

“We have an obligation to maintain a competitive team,” Angelos said. “To trade Wells would have had a very detrimental effect. There is still almost a third of the season still to play.”

While the Orioles stood pat – and infuriated general manager Pat Gillick – the Yankees dealt for home run machine Cecil Fielder and looked to pad their then rare lead in the American League East.

And then the strangest thing happened to a team of underachievers with the Baltimore Orioles.

The team started winning.

The Orioles won four in a row and then five in a row later in August, as the bullpen got healthy and the bats came to life. During Labor Day week they beat up on Detroit and Chicago and positioned themselves back into the hunt for an orange October for the first time since 1983.

But even the players felt the strangeness of being members of the Baltimore Orioles. Because Angelos had appointed numerous members of his family into key roles, it seemed that everyone had an opinion. After Bobby Bonilla hit a key home run in September and trotted around the bases he soon heard from the clubhouse attendant, who answered the clubhouse phone. “Mrs. Angelos called and said your shoes are a little too loud, a little too showy,” the message was delivered. “She wants you to change your shoes.”

Bonilla, like many of that generation, were showing off all kinds of shiny new kicks that apparel companies were trying to get them to showcase.

And if the opinions of Mrs. Angelos, which according to many came frequently and from the beginning on all sorts of issues from interior design to uniform colors and patterns to the annual selection of the picture for the cover of the Orioles media guide, were a little awkward for the players, you can only imagine the frost that came when Gillick was overruled by Mr. Angelos.

But it turned out that the owner could later brag about being “correct” regarding the July 31st prescription to not trade Bonilla and Wells. It also didn’t help interior harmony when the players found out that their GM didn’t want them anymore.

Gillick later addressed his relationship with Angelos in The Baltimore Sun: “We’ve had discussions, and we’ve had heated discussions. The only time we really had a major disagreement in policy was in July . . . He thought the baseball people were looking forward to ’97 and forgetting about ’96. I respect where he’s coming from. I understand where he’s coming from. Sometimes, it’s good to have his perspective. I don’t think there’s anything wrong with us not agreeing on certain issues. I think that’s healthy.”

But it was on September 27, 1996 when Angelos would once again exert himself into the conversation in regard to a player’s actions on the field.

In Toronto, where he lived and played for two World Championship teams, Roberto Alomar got into a heated argument at the Skydome over a called third strike with veteran umpire John Hirschbeck and blatantly spit in his face after the words were exchanged. Hirschbeck was going through a rough time in his life with the death of a child from adrenoleukodystrophy (known as ALD) and another child had been diagnosed with the disease. Afterward, Alomar referenced this situation as a perhaps a reason that Hirschbeck was so confrontational and maintained that Hirschbeck used a gay slur in their conversation. Alomar said he spat at his face to respond to the lack of respect.

For Major League Baseball, this was an ugly episode that took months to untangle and the fact that Hirschbeck went after Alomar in the bowels of Skydome after the game and threatened to kill him made the situation worse. It was the lead story on ESPN and every news outlet and it sullied Alomar’s otherwise strong reputation in the game that would eventually lead him to Cooperstown. He was already well on track to a Hall of Fame career and this was a black eye for him and the sport as a whole. And with just two games left in the season and the Orioles having made a miraculous comeback to qualify for the playoffs, Alomar was widely made a villain by the national media.

The next weekend, Alomar hit a 10th inning, Game 4 home run in the American League Division Series to give the Orioles a dramatic 3-1 series win to advance to the AL Championship Series where they lost in five games to the New York Yankees.

Alomar rose to the occasion at Jacobs Field in the ALDS despite being showered by boos from the Cleveland fans, who hated everything about Baltimore in 1996. The Baltimore Ravens were just five games removed from being the Cleveland Browns and this series was quite hostile given the civic temperature in Northern Ohio.

Angelos spent the offseason investigating the spitting incident and commissioner Bud Selig suspended Alomar for the first five games of the season. But the Orioles owner made sure the public knew that he’d be paying his second baseman his full salary because he felt that Alomar had already been punished enough in the court of public opinion. As much as owner-player relations were strained during the 1994 strike, this dispute directly involved the usually silent third party of Major League Baseball: the umpires.

The coziness of Selig’s ability to usurp the commissioner’s office had really placed the umpires in a bad spot when there were problems on the field.

But, once again, it was Angelos who came to Alomar’s defense publicly in The Sun and along with the player’s agent made a very public statement that Hirschbeck should apologize to Alomar for taunting him.

“If you take literally what he said to the kid, he accused him of having a sexual relationship with his mother,” Angelos told the paper. “Now, just because it’s used a lot, rarely does anyone make that statement to anyone in a confrontational manner. And in this case, it was.”

Angelos said Hirschbeck should be “man enough” to admit what he said to Alomar, calling his player’s reaction “unfortunate but understandable. If you say something to a 28-year-old athlete like that, you can understand that’s going to be the reaction. Probably Robbie wanted to take a poke at him, but he couldn’t reach him, and he did the next best thing. His reaction makes no sense unless you understand the context. If you look at the record, John Hirschbeck is a fine, upstanding individual and Robbie has been, too. There are those saying, ‘Let’s forget about it and move on.’ Yeah, but it’s forget in a fashion that is unacceptable to those who seek the truth and want to know exactly what happened. There is a gross injustice here.”

Richie Phillips, the umpires’ union general counsel and an umpire himself, went nuts. “Selig should say, ‘We have the finest umpires in the world, and we’re going to protect them and deter players from abusing them, especially physically.’ We had an agreement with the commissioner’s office not to engage in public rhetoric and the next thing we know, Angelos is saying he’ll pay Alomar even if he’s not compelled to. On top of all this, the straw that broke the camel’s back was Angelos saying John Hirschbeck should apologize to Alomar. Selig again did nothing, even though people in baseball urged him to act. A substantial fine should have been imposed on Angelos.”

Alomar and Hirschbeck made very public apologies to each other on April 22, 1997, standing at home plate where they shook hands at Camden Yards. They joined forces to raise awareness about ALD and to raise money for research and spent years publicly attempting to right the wrong and work together. “God put us maybe in this situation for something,” said Alomar in later years and always made a point to refer to Hirschbeck as “a friend.”