Perhaps the saddest part of the celebration in Tampa, and probably something most outsiders don’t know, is the fact that the team never had a moment alone together after winning.

After being holed up in a fully guarded hotel for an entire week, after working through training camp and practices, game study and film watching, eating and traveling together for a full season, and becoming road warriors in the postseason, the post-Super Bowl celebration offered them no “special moment” as a family.

Amidst their own families and media, the fans and confetti, the emotions and the mayhem, and the field being swarmed with humanity, the separation of the 2000 Baltimore Ravens began the instant the clock hit zero, and the fireworks began.

At one point, about 30 minutes after the game, owner Art Modell addressed some members of the team in the winning locker room, but many players were missing. They were getting injury treatment. They were kissing their family. They were doing interviews. They were in the shower.

There were, however, some wonderfully emotional moments.

Duane Starks and Ozzie Newsome exchanged hugs and remembered the genesis of their relationship.

The tears of Phil Savage as he held Anthony Poindexter in his arms, remembering seeing that video of the injured safety on the roof in San Francisco.

But those moments weren’t shared en masse, as a group of men who had been through so much fully deserved. And they never will be.

Billick knew prior to the game what to expect, and took the final opportunity to address his men in the tense moments before taking the field hours earlier. It was a very emotional address and, for some, a final farewell.

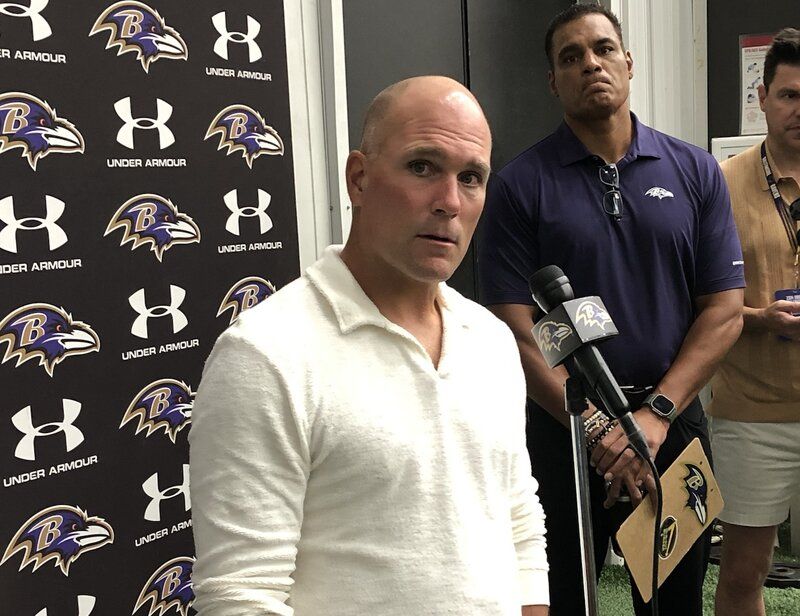

“I told them to look into each other’s eyes and remember it,” Billick said. “I told them, ‘This family is never going to be the same again. Your lives will never be the same again.’ ”

With free agency, salary cap implications, the draft and the nature of the NFL in the new millennium, the 2001 Baltimore Ravens would be a different group of players.

“With all of the outside influences they knew it was true,” Billick said. “But I wanted them to know that for one final day, for that period of time, we were going to be a family one final time. I said, ‘Take it for what it is and relish it, because you’ll never have it again the way it is right now.’ ”

His words were prophetic.

Within six weeks of the Super Bowl, quarterbacks Trent Dilfer and Tony Banks knew they would not return to Baltimore. Center Jeff Mitchell would sign with the Carolina Panthers. Safety Kim Herring signed a free-agent contract with the St. Louis Rams. Harry Swayne would not be returning.

Instead, the following season it would be Elvis Grbac at quarterback, Leon Searcy at right tackle and a whole host of other new faces in Baltimore.

As for my emotions, I managed to hold them in check throughout the fourth quarter of the game, exulting a few times and just screaming at the top of my lungs for no good reason. By game’s end, I managed to move from my lower end zone seat to the 50-yard line, about four rows behind the Giants bench. Unlike many Ravens fans, who went behind the wrong bench (if you were behind the Ravens bench you were behind the giant Lombardi Trophy and getting a rear view of the ceremonies), I had a crystal-clear view of the moment every Baltimore football fan had waited nearly a lifetime to witness. The presentation of American sports’ largest honor – the NFL’s Lombardi Trophy – was a sight to behold.

It was the first time I had ever not been on the field at the conclusion of a Ravens game. The NFL wouldn’t give me a pass. I thought I would be disappointed not being down in the mix near the podium, but I couldn’t have been more wrong. Seeing it from the perfect distance, I raised my arms in triumph and thought about how fate and one man’s decision – the decision of Art Modell to move his NFL franchise to Baltimore – had so greatly affected my life.

I realized the pain of the Cleveland fans at that moment and I empathized. But I thought more about my own good fortune – my radio show, the path it took me on, my radio station, my national show, the trips, the friends, the fans, the memories, my lifestyle, the fun – and I could trace much of it back to the day that the old, silver-haired warhorse showed up, looking bewildered and lost, in parking lot D of Camden Yards more than five years earlier.

I managed to keep my composure during the dedication by commissioner Paul Tagliabue, who was booed so loudly I couldn’t even hear his speech. I heard Art Modell speaking, then Billick being questioned by CBS’ Jim Nantz.

Just then, as Billick reached for the Trophy and hoisted it skyward, I began to sob. Uncontrollably.

It was then that I thought about my Dad, and how much I missed him at that instant. I thought about John Steadman. I thought about the first time I met that tall stranger, who was now standing on the podium with the Lombard Trophy. I thought about Kevin Byrne, and all of the times I’d bugged him for information about the team. I thought about how this might never happen again, and if it did, it probably wouldn’t feel the same way.

You know how it is when you get that emotional baggage going, it becomes a downhill train rolling out of control. You can just wreck yourself with the deeper meaning of it all.

I composed myself, headed for the locker room and spent an hour congratulating all of these guys who had made it so special, so much fun for me to know them and be a true fan.