While the coaching philosophies of Marchibroda may have failed the Ravens in their early days on the field, it was his draft philosophy that netted quality football players and served them well in winning the Super Bowl in their fifth season.

Marchibroda’s meeting with Newsome and Savage that day in Baltimore included two written statements that formed the credo of all draft-day procedures in the war room.

Marchibroda’s mandate: “Let’s utilize our scouts’ knowledge and research into the players’ intelligence levels, attitudes and backgrounds. That’s why they are being paid.”

In the past in Cleveland, under the Lombardi administration, the scouts’ information was not taken seriously. Craig Powell and Antonio Langham, the first picks of the previous drafts, would be ample evidence that scouting needed to be taken more seriously on Draft Day if this organization was to move forward in Baltimore.

Savage and Newsome wrote a mission statement that first day that serves the team well to this day:

“To thoroughly evaluate draft eligible prospects and then select the most talented player who possesses character and a football temperament.”

Marchibroda said it simply: “Get me some good players with good character who love to play the game of football.”

“It was such a common sense approach,” Savage said. “But sometimes it’s overlooked by everything happening on the outside. Ted Marchibroda without a doubt had an influence on the championship we won. He won’t get much credit, but he certainly deserves it.”

Newsome and Savage have been universally praised and given that credit throughout the NFL world for their deft handling of the five drafts that produced a Super Bowl championship. Even before the Ravens won that day in Tampa, they were heralded as much for their late-round gems as much as not missing on the blue-chip first-rounders. But don’t kid yourself. As easy as it sounds on Draft Day, and as easy as Mel Kiper makes it sound on ESPN on that Saturday morning in April, if it were that easy the word “bust” would refer strictly to a woman’s bosom.

Take the “other” part of the 1996 draft, the one that had already produced a pair of future Hall of Famers in the first round.

In the middle of the second day of the draft, Newsome was determined to add some spice to the special teams unit and find an Eric Metcalf-type who could break open a game with a touch of the ball.

Newsome had already identified Jermaine Lewis out of the University of Maryland as a candidate. A tiny, waif of a man even by man-on-the-streets standards, Lewis was all of 5-feet-7 and 165 pounds, but Newsome said in the middle of March that he was “going to steal that kid in the fifth round.” While on the clock with the 153rd pick of the draft, Newsome phoned Lewis’ home only to find that he was at the movies with friends. Sometimes it makes teams nervous – “you always want to talk to the kid just to make sure he’s actually alive before you draft him” one scout said – when the prospect isn’t readily available. Even so, Newsome took the diminutive wide receiver and special teams wonder and he was still paying dividends on the field at Super Bowl XXXV.

That’s the good news.

Three of the other four picks of that draft never did contribute much in Baltimore or anywhere else in the NFL. Dexter Daniels, James Roe and Jon Stark will be names for the small type of a future Ravens’ media guide.

The other pick, DeRon Jenkins – a second-round cornerback taken at No. 55 that the team had in its Top 20 that year – had the Ravens so excited that they gave away a third- and a fourth-round pick to move up. Jenkins played a few up and down seasons in Baltimore before his exit for San Diego and a monster deal in free agency. He struggled as a Charger in 2000 and was cut immediately following the season. The jury is still out on the wisdom of that selection.

Despite the significant contributions of Jonathan Ogden and Ray Lewis in their rookie season, the team went 4-12 and consistently fell apart during the fourth quarter of games on the defensive side of the ball. No lead was safe. No down and distance could get the defensive unit off the field. The Ravens lost seven games that season when they had third-quarter leads, and surrendered a whopping 130 fourth-quarter points.

Newsome trashed most of the players from that defense and began building the foundation of the greatest defensive unit in the history of the game (165 points surrendered in 16 games in 2000) around Lewis during the spring of 1997 with a combination of deft free agent bidding and a hot hand on draft day.

Within a three-week period in April, Newsome signed both defensive end Michael McCrary and defensive tackle Tony Siragusa for deep discounts late in the free agent game. Both were coming off decent seasons and had been left in the trash heap after other NFL teams had doled out huge dollars to more attractive players earlier in the signing period. Keep in mind, the Ravens were in a terrible financial pinch – both in liquidity for signing bonuses and against the league’s salary cap – after the move from Cleveland. There was no way they could’ve played in the primary free-agent market in their financial condition, so Newsome was strapped.

McCrary had just become a starter for the Seattle Seahawks and ended his first full year with 13.5 sacks. He was thought to be undersized and a product of a system that was set up to create double teams on other linemen. Newsome convinced him to take a back-loaded deal predicated on immediate production and a chance to play near his hometown of Vienna, Va.

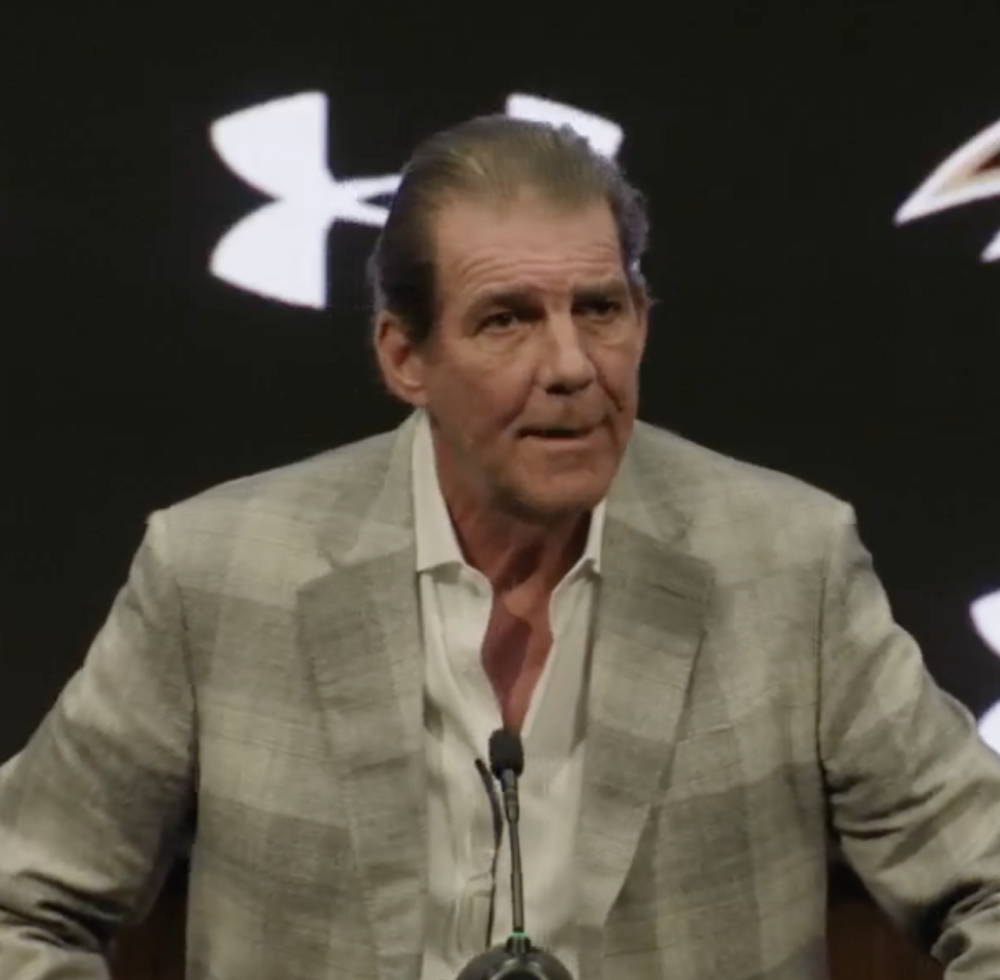

Siragusa was a different story. “The Goose” was aggressively recruited by former Indianapolis boss Marchibroda to bring leadership and intensity to the defensive huddle. He also came cheap with a history of nagging knee injuries and a battle to keep his weight down that scared off the Colts from a large salary.

Between the signing of those two future champions, Newsome and Savage had a draft to run. With all due respect to their impressive rookie foray into the war room, it was Saturday, April 19, 1997, that would ultimately be the biggest day personnel-wise in molding the defense that would change the course of history for the franchise. The duo went into the draft armed with 12 selections and left with a full cupboard.

The selections of linebackers Peter Boulware and Jamie Sharper, along with safety Kim Herring, over a five-hour period that day would four years later earn them a passage to the Vince Lombardi Trophy. Not only did all three start, play well and bring unbelievable character and intelligence to the field, but their speed blended perfectly with what defensive coordinator Marvin Lewis needed to partially re-enact the Steeler defense that he cut his teeth on two years earlier at the Super Bowl.

Oddly enough, the courting of both Boulware and Sharper began on the same day at Doak Campbell Stadium in the Fall of 1996, when Savage and his father, Phil Sr., stood on the sideline of the Florida State-Virginia game and Savage immediately noticed the junior Seminole’s speed rush and motor. “It was impossible to miss (Boulware) because he was just flying all over the field,” Savage would later say. Boulware was known as a quality student and didn’t seem too likely to skip his senior season, and quite frankly, his teammate Reinard Wilson was generally considered the better prospect before the season began. Boulware finished the game with three sacks and ended his junior year with 19 sacks.