I had tried it both ways and I decided if I was going to go down as being “unprofessional,” or snickered at by a bunch of media dorks, I was going to go down on my own terms and clearly having more fun than any of the rest of them.

I was a “true journalist,” I believed, just with a different wardrobe.

Did my wearing a purple Ravens official team issue jersey and a $19.99 Ravens’ “flying B” hardhat and blowing a “Raven caw” whistle have anything to do with the questions I’d ask, the stories I’d report or the “insider” information I’d get from the players in the locker room?

I didn’t think so.

But Matt Stover did.

“Take off that stupid hat, man,” Stover said to me, in a not so pleasant fashion. “You’re in the locker room. If you’re in the media, act like a professional.”

Wow, I’d officially been admonished by a player, a kicker no less.

“What a dick!” I thought to myself.

If the little guy is going to scream at me after winning a game, what’s the big angry dude in the corner going to do? Eat me like Hannibal Lecter?

(It should be noted that Stover and I quickly came to a détente less than two weeks after the “incident” and share quite a healthy relationship. Like many others, he came to see it my way on the wardrobe choice.)

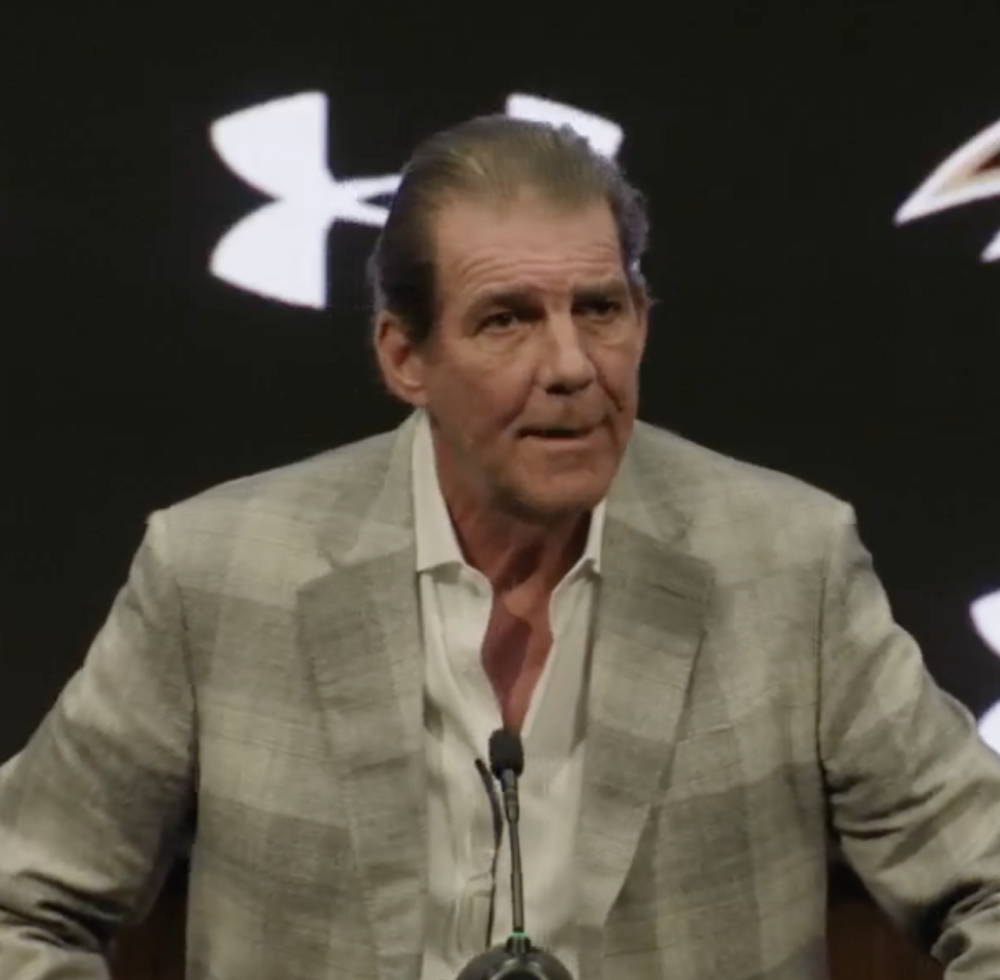

Lewis was in the corner of the room on the left, no more than 20 feet from Stover in the cramped room. Equipment was strewn all over the place and players were cutting all of their tape off and trying to make their way to the shower. He was all alone, catching his breath when I approached him.

“Hi Ray, my name is Nestor Aparicio and I host a radio show in town,” I said.

“Hey buddy, how you doing?” he said in that high-pitched, soft lilt that he’s now famous for. For the record, “buddy” is Ray Lewis’ favorite term of endearment.

“I’m sorry I haven’t met you before,” I continued, “but I’m starting this Monday night radio show at a restaurant here in town and I was wondering if you’d like to be my first guest. You had a great game and I’d like to buy you a crab cake.”

“What time is it?” he said.

“Around six o’clock, whenever you can get there, really.”

“Just write some directions down and I’ll be there for you,” Lewis said.

It was that easy. The next night Lewis came to The Barn and received a warm welcome and answered phone calls from Baltimore football fans for nearly two hours.

He talked about work ethic, winning football, the fans of Baltimore, his friend Marlin Barnes, and he actually laughed once when I compared him to Lawrence Taylor and made a reference to him being a Hall of Famer. The biggest story of the first game for the talk show fodder was the double-armed pump to the sky he would enact after making big plays against Oakland. He called the “raising the roof” motion, “The Train,” after the popular song by the Quad City DJs. To no one’s surprise, the song and the theme caught on for the team during its maiden season.

After the show that night, I taught Ray Lewis how to eat crabs downstairs at The Barn after he admitted on the air that he had never tried one. At first, he scoffed, calling it “too much like work.”

Lewis came out to The Barn three more times that season for my show and actually became a fixture in the restaurant downstairs, falling in love with the distinctly Baltimore tradition of eating crabs and having a few beers. Once he became a Baltimore icon, he would insist on carry-out crabs so he could enjoy them at home with his family.

Perhaps the scariest moment of Lewis’ career – maybe even more scary than the infamous arrest and murder charge in Atlanta that would follow almost three years later – came on the practice field at training camp in Westminster the following summer.

While running through drills on a sweltering afternoon, a since-forgotten fullback out of Southwest Louisiana named Kenyon Cotton rolled through the defensive line and had a head-on collision with Lewis. Suddenly, for more than a brief moment, everything in the organization stopped.

Lewis lay motionless in the middle of the field and trainer Bill Tessendorf and his staff ran feverishly to him. He was numb. Minutes later a helicopter would arrive and transport the future Hall of Famer to the University of Maryland Shock Trauma unit. The scare – which wound up being a nasty “stinger” – seems a distant memory now, but for a few frightening hours, Lewis’ career appeared in jeopardy.

During that second season, Lewis would seal the fate of the greatest win in Ravens history prior to the Super Bowl season, at least in the mind of the locals.

With the game on the line at the newly anointed Jack Kent Cooke Stadium on Oct. 26, 1997, and a 20-17 lead about to unravel, it was Ray Lewis who intercepted a Gus Frerotte pass just inside field-goal range in the final two minutes to seal the victory over the hated Redskins. The next night Lewis shepherded running back Bam Morris, who had rushed for 176 yards and a touchdown at Washington, over to The Barn for his first appearance on my show.

Morris was very sheltered during his time in Baltimore. A multiple offender of the league’s substance abuse policy, Morris had been found with a trunk load of marijuana just a few months after playing in Super Bowl XXX while playing for Pittsburgh and had again found trouble by drinking when it wasn’t permitted under league aftercare guidelines.

Showing the leadership side of his personality and wanting to help the team and Art Modell, who had been so loyal in giving Morris a second chance, Lewis took it upon himself to be Morris’ constant companion and youthful mentor. Lewis, despite being just 22 years old himself, wanted to be a role model for the older, troubled back and keep him on the straight and narrow.

At one point later in the season while celebrating at a post-game party on a Sunday night on the city’s west side, Morris again found his name in the wrong place in the Monday morning newspaper after getting into an altercation with a woman who was linked to teammate Derrick Alexander. It was a tangled mess that included Morris’ wife as well as the police. Alexander and Morris feuded privately, dividing the clubhouse, and Alexander found himself on the bench for a game in Jacksonville and, eventually, both wound up out of the organization. Coincidentally, they both surfaced in the same place, Kansas City, the following season.

The day after the incident, Lewis came to The Barn to do my show and confided in me that he always tried to keep Morris out of trouble, but the Texas Tech grad couldn’t help himself. He had no self-discipline at the dinner table or when it came to partying. Lewis was disgusted with Morris and threw his hands up in the air.

“I told Bam that nothing good is going to happen to you going to parties after games,” Lewis told me privately while dining on some crabs. “I told him, ‘You should stay home, mind your own business and be boring. That way nothing bad is going to happen and you stay out of trouble.’ But he doesn’t listen. He’ll never listen.”

Later in his career, Lewis could have used his own sound advice.

People ask me all the time, especially after the Atlanta Super Bowl incident and the murder charges, “What kind of a guy is Ray Lewis?”

The Ray Lewis I knew was always considerate, thoughtful and loyal to a fault.