Baltimore not only had a grass field and a new stadium, but a defensive system that Lewis had in place to immediately make him comfortable. The previous two drafts provided the unit the best young talent in the league with Ray Lewis, Peter Boulware, Jamie Sharper and Kim Herring all coming into their own. Ray Lewis and Boulware were both represented by Woodson’s longtime agents, Roosevelt Barnes and Eugene Parker, so he knew the whole story.

“It wasn’t about talking Rod into coming because Rod couldn’t be talked into anything,” Marvin Lewis said. “He looked at everything and when we told him he’d be able to go home every Sunday night after games to be with his family until Wednesday morning, we had something no one else could offer.”

If there’s one trait that Woodson shared with his future teammates in Sharpe and Ray Lewis, it was a love of the gym and fitness.

HEAR NESTOR CHAT FROM THE BARN IN NOVEMBER 1998 WITH ROD WOODSON AND RAY LEWIS HERE:

“He was always nicked up in Pittsburgh,” Marvin Lewis said. “He was never 100 percent. But he would work out like you wouldn’t believe. One time he got me on a treadmill in Pittsburgh and he tried to kill me.”

The defensive side of the ball began to flourish in 1998 despite Woodson’s age on the corner. Ironically, it was in 1999 that he experienced his biggest setbacks initially, moving inside to the safety position where it was obvious he was tentative at first.

But a few weeks into the season he adjusted nicely and his influence on the three young cornerbacks of that year’s team – Chris McAlister, Duane Starks and DeRon Jenkins – became immediately clear.

“He brought stability to the secondary,” defensive end Rob Burnett said. “He taught those guys how to study, what to look for. Rod makes his living by cheating because he knows teams’ tendencies and formations. He sees things that he’s been watching on film all week, then – bam – he goes and gets the ball. He knows what’s going to happen before it happens and he’s taught some of that to Chris and Duane. He’s a leader. He does his job and then some.”

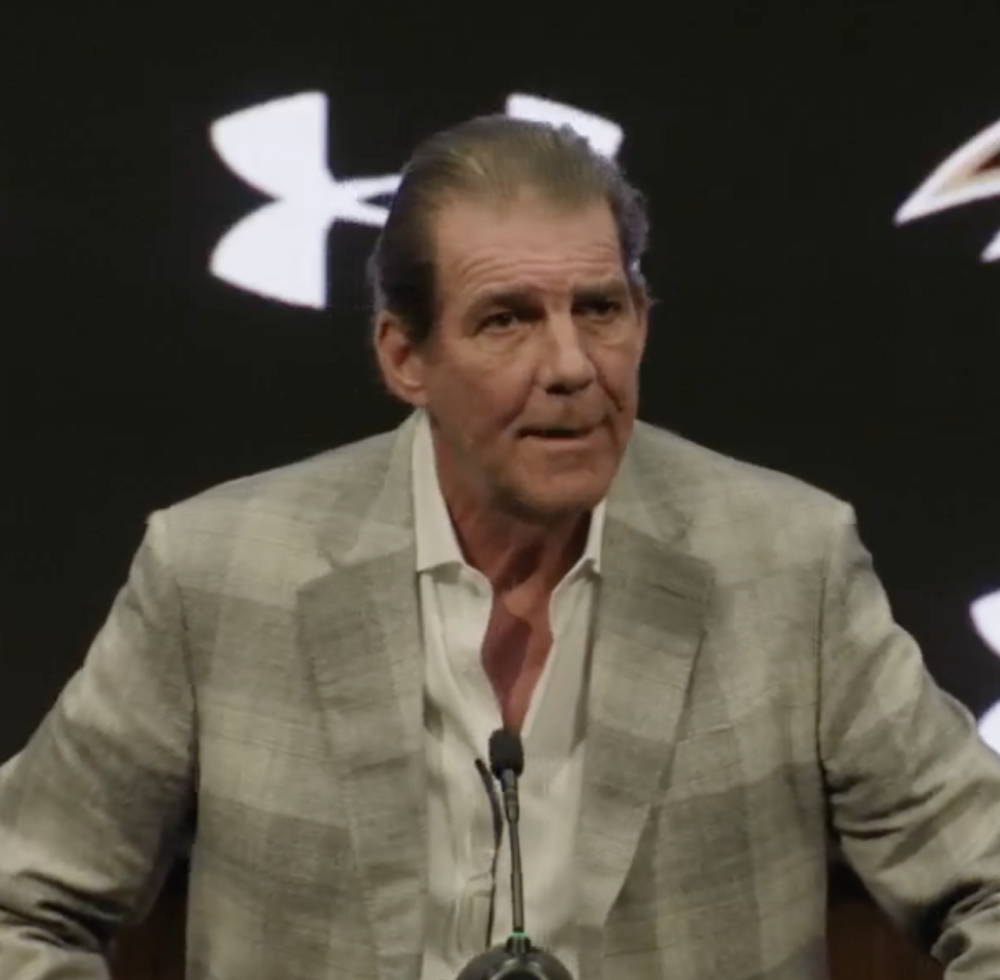

The leadership that he brought to the defense was not lost on head coach Brian Billick, coming off an 8-8 season in 1999.

“Besides being a consummate professional, which is a (great) example for the entire team, what has Rod Woodson not seen on game day?” Billick told The Sun. “What situation has come up, what route combination, what critical situation has he not seen? I can’t imagine. So there’s that rock back there for them … Everyone needs someone to lean on, everybody needs someone to look to in times of crisis. They know they can look for Rod Woodson because he’s been there, done that and seen it all.”

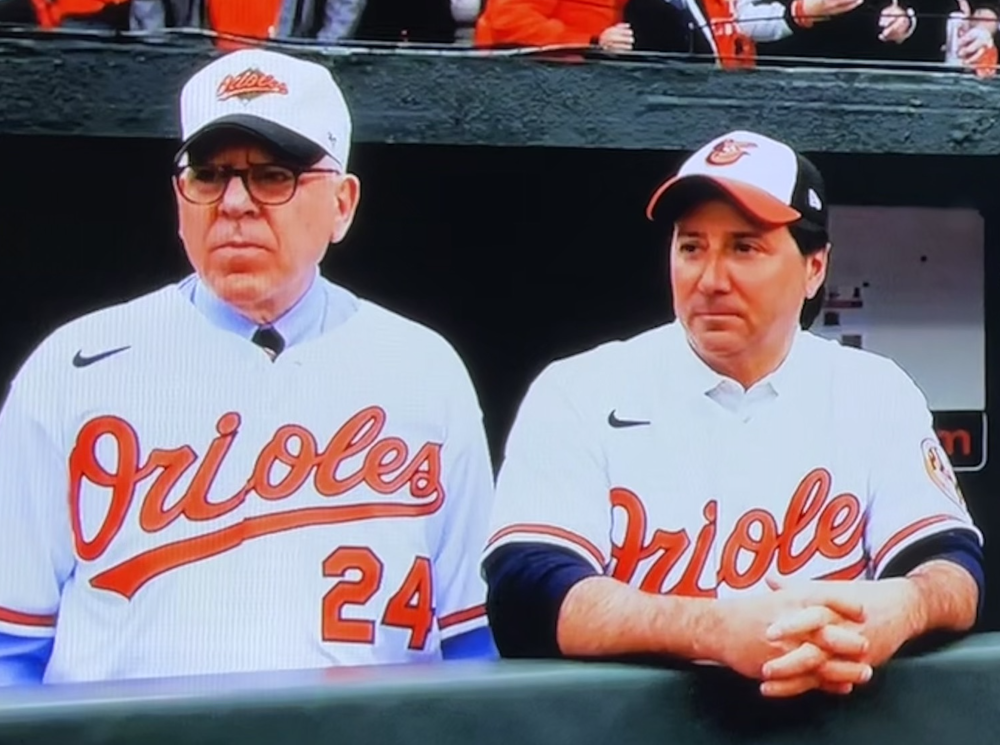

With the infusion of cash into the organization after owner Steve Bisciotti became involved, Billick and Newsome had the resources available to go into the marketplace and shop on the top shelf, instead of bargain hunting, for that type of player for the other side of the ball.

A former college tight end himself, Billick always had utilized the odd position in complex ways in his offensive game plan, including a dynamic two tight-end set.

In 1999, he was handcuffed by the lack of ability in that department with the likes of Greg DeLong, A.J. Ofodile, Lovett Purnell and Ryan Collins. The franchise had never had a quality, consistent tight end since the departure of Ozzie Newsome in Cleveland in 1990. While in Baltimore, the team had taken a look at an aged Eric Green, an undersized Brian Kinchen and such luminaries as Cam Quayle, Scott Richards, Bill Khayat, Themba Masimini, Harold Bishop, Frank Hartley and Jesse McCovery.

Billick decided that his first move to strengthen the team was to look for help at his old college position. Securing future Hall of Famer Shannon Sharpe wouldn’t be cheap, but he would be worth every penny of the investment.

“Ozzie and (Sharpe’s agent) Marvin Demoff have had a long-standing relationship and we made it very clear that this would be a team where he could have some impact,” Billick said. “We needed to know the price and whether or not he was damaged goods.”

Sharpe had played in just five games during the woebegone 1999 season for the Denver Broncos, who were coming off a pair of Super Bowl titles and flopped to a 6-10 record after a series of key injuries and the loss of quarterback John Elway to retirement.

Sharpe fractured his left clavicle in early November that season and never fully recovered.

He was nearly 32 now, twice a champion, a very wealthy man and obviously had a future in the media. He had been to seven Pro Bowls. He was already doing national television spots as a pitchman for a mutual funds company. His brother, Sterling, a former wide receiver for the Green Bay Packers, also had a budding career in television with ESPN.

Would he be hungry enough to come to an up-and-coming team and make a difference?

And what kind of money would he command?

“From the minute we met it was a complete synergy,” Billick said. “We were all truly on the same page.”

The dividends that Sharpe paid on the field – a game-winning catch vs. Jacksonville in the second game of the season to beat a franchise that previously held an 8-0 advantage in four seasons, the 96-yard touchdown reception in the AFC Championship Game in Oakland that took the team to the Super Bowl – paled in comparison to what Sharpe did long before he even pulled a purple jersey over his head for the first time.