4. The Dumb Dumb error begins in Baltimore

“I don’t think any boss, anybody in charge should ever criticize subordinates publicly. That is even in this business here that Frank Sliwka operates [at The Barn in Carney]. If he has a problem with one of the employees I think he should take them in the back room quietly and tell should tell him or her what he objects to. I don’t think anyone should publicly chastise an employee. When you’re a boss you keep that kind of thing to yourself. And that’s what I said to Davey Johnson. And I’ll repeat it again and I’ve told him that since then. He’s a great manager. He’s a great guy. I love him like a brother and we get along fine. Except I’ve said to him, “If you have to criticize someone, you take him in your office, shut the door and let it be between you and the player.”

– Peter G. Angelos on WWLG Budweiser Sports Forum

March 1997

THERE COULD BE NO ENCORE for an act and a night as emotionally charged as the Cal Ripken 2131 night at Camden Yards in September 1995. Once again, there was no postseason baseball in Baltimore for the 12th consecutive year and Angelos, aided by the immortal Iron Man streak and the intense, family-like local passion for baseball, had enough revenue coming into the franchise to afford any baseball player he wanted in the marketplace. The club was swimming in money vs. its MLB foes. Plus, given his pro-player stance in the contentious labor dispute, many believed the Orioles would be a haven for free agents who wanted to sign with an owner who saw their side and wanted to win and put the best team on the field.

Looking ahead to the 1996 season, Peter G. Angelos was obsessed with one thing: bringing a World Series to Orioles fans.

Immediately following the 1995 campaign, Angelos fired manager Phil Regan and “accepted the resignation” of Roland Hemond, who was actually forced out, along with Frank Robinson, who was glad to leave the Orioles at that point and wound up working for commissioner Bud Selig in the MLB office.

Angelos was clearly running every aspect of the Baltimore Orioles at this point and was quite brazen in the media regarding his daily involvement. He bragged that he had enough time to run a law firm that was netting more than $15 million per year in personal income for him at the time and a MLB team on the side. Now with all of the “baseball people” gone except for his self-appointed farm director Syd Thrift, Angelos needed a new manager and a new general manager. He had already developed quite a reputation in the insulated, incestuous world of baseball men and lifers. He had owned the team for less than 24 months and had already pissed off every one of his 27 MLB partners, upstaged Cal Ripken on the biggest night of his life on national television and chased off two managers and a total of five baseball men: Roland Hemond, Frank Robinson, Doug Melvin, Johnny Oates and Phil Regan. Together they spanned three generations of baseball and touched virtually everyone in the industry with their true stories of an owner who called a manager into his office and demanded – among other things – which third basemen would be in the lineup on any given night.

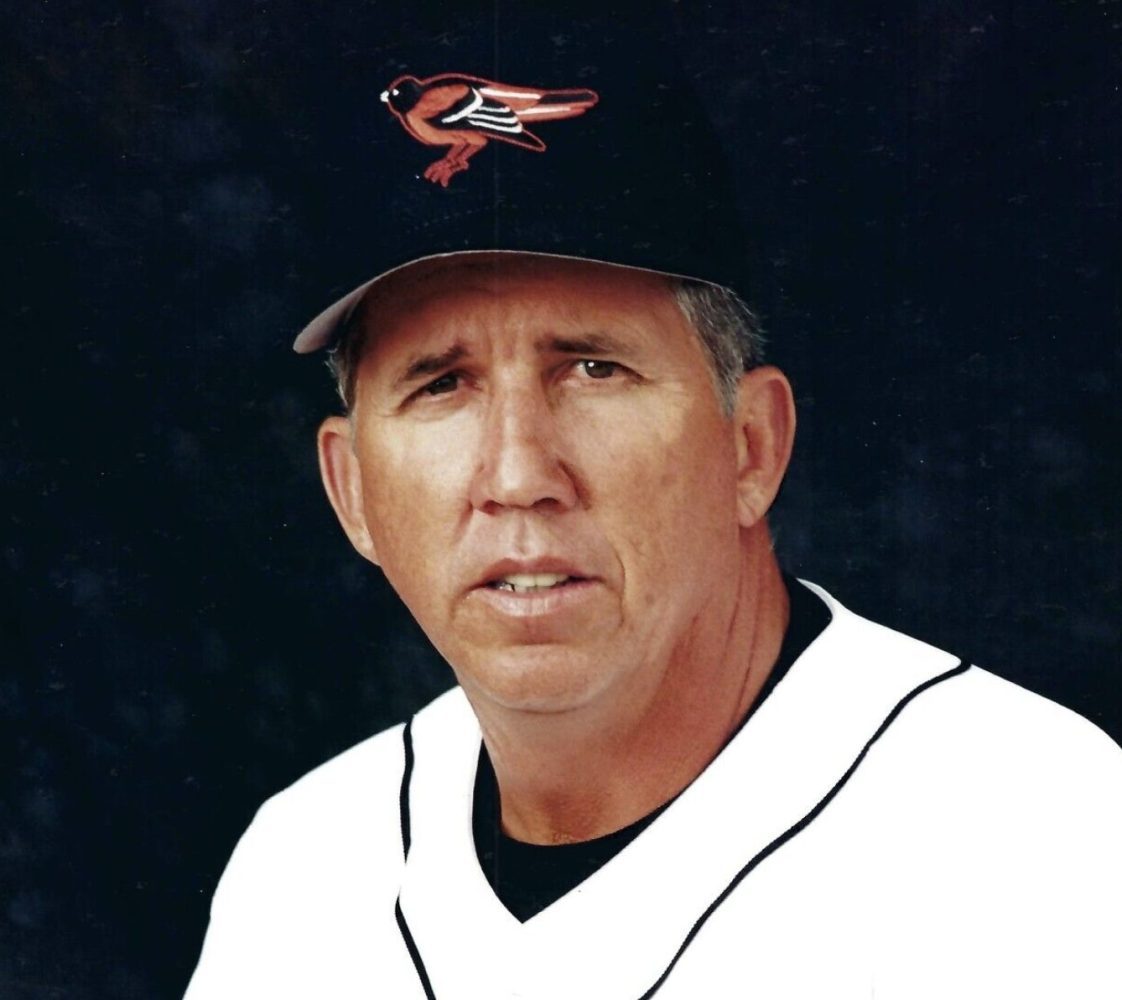

A year earlier Davey Johnson, a former Orioles second baseman and World Series champion as manager of the 1986 New York Mets, was interviewed by Angelos and his internal committee that included Joe Foss and team lawyer Russell Smouse, but they instead selected Phil Regan, who they thought would be a hot commodity the previous year and whom never was given much of a chance under Angelos.

Johnson, who had a storied reputation for being snarky, cunning and anti-authority, took a shot at Angelos 12 months earlier when he didn’t get the job: “I heard they wanted an experienced manager and a proven winner. That’s why I interviewed for the job. But I guess that’s not what they wanted, right?” he told the media when he was clearly disappointed that he wasn’t selected in October 1994.

Now, after a disastrous year on the field in 1995 under Regan, Johnson’s name surfaced again and Angelos wasted no time in complementing the decorated yet difficult managerial prospect stating, “His baseball knowledge is impressive, and his strong background with the Orioles came through.” Johnson, meanwhile backtracked from any contentiousness in an effort to get the job: “I enjoyed meeting Peter,” he said. “You read stories about the Big Bad Wolf, but he was really nice.”

On October 30, 1995, Johnson was named manager of the Baltimore Orioles, the club’s third skipper in just 18 months under the Angelos regime. “This is a move in the direction of producing a winner,” Angelos said. “We are committed to building a winner in Baltimore, and Davey is a vital part of that effort. He has a winning attitude. He’s a very down-to-earth, forthright baseball professional with an extensive knowledge, and his record clearly establishes that.”

Was Johnson still sore about being passed over the previous year? “I do have a lot of pride, but I don’t have a big ego,” Johnson said. “Maybe I was hoping they’d offer the job so I could say no, but I discarded that idea in about two seconds because Baltimore represents my baseball roots. I thought it was a good fit a year ago, and I still do.”

Angelos allowed Syd Thrift to represent the Orioles at the MLB meetings in Arizona while he remained in Baltimore to interview a bevy of candidates to be the next general manager. Kevin Malone, a former Montreal Expos general manager, and Joe Klein, who had local roots and had been the GM of the Detroit Tigers, were considered to be the front runners but much like with every baseball decision made by Angelos, time wasn’t considered a pressing concern.

And despite most legitimate general managers wanting the opportunity to hire a field manager, Angelos did it backwards. The new manager, Davey Johnson was sent off to the MLB winter meetings along the farm director, Syd Thrift. Both were encouraged by Peter Angelos to recruit an appropriate general manager and working partner that would bring the Baltimore Orioles a World Series title.

In Phoenix, Johnson tracked down former Toronto general manager Pat Gillick, who was his old minor league teammate from Elmira in 1963, and tried to talk him into coming to Baltimore as the general manager of the Orioles.