“They told me I’ve got to pick and choose and kind of balance off (how many hits I take). But I don’t know, I kind of like it. I’m much more sore this way, but I kind of give more hits than I take.”

–Jamal Lewis, Sept. 25, 2000, Coors Light Monday Night Live show from The Barn as heard on WNST-AM

Two things were pretty obvious to everyone who watched the 2000 Baltimore Ravens during the first half of the season. When they passed the ball, they made mistakes and were ineffective. But each time they tried to run the football with any consistency, they succeeded.

It was pretty obvious to even the most casual observers, after nearly 21 quarters of not scoring a touchdown, that this was an offense in need of a retooling, if not a revamping.

Head coach Brian Billick’s mantra coming in from Minnesota was to have “explosives” in the offensive playbook. He would bore the media to tears with statistics and the use of fancy ideologies but it was just his grown-up terminology for calling “The Bomb.” Just like we did in the backyard as kids.

He had it in Minnesota with Cris Carter and, more recently, Randy Moss. He had strong-armed quarterbacks like Warren Moon, Brad Johnson and Randall Cunningham who could deliver the ball 65 yards on a rope.

In Baltimore, Banks could throw the ball 65 yards but it was apparent that he didn’t always have command of where the ball was going to land. You could trace the first three losses of the season – Miami, Washington and Tennessee – directly back to one poor decision or one poor pass that Banks had thrown.

As for Dilfer, one look at his wobbly passing efforts on a windy day against Pittsburgh made it very clear that throwing the “20-yard out” – perhaps the toughest pass for a quarterback to throw in the NFL because of the speed of cornerbacks to get a jump on a slow-moving play and making a run at an interception – would be a challenge. Dilfer was a leader, an emotional man with a passion for the game and the ability to take direction from his coaches. Dilfer was also egoless about his statistics. After being unceremoniously thrown out of Tampa in 1999, Dilfer just wanted to play and win.

If Billick was going to stick with Dilfer – and at this point halfway through the season with a neophyte third-stringer in Chris Redman on the bench, what other option did he have? – he was going to have to alter his well-thought-out philosophy on how to get a defensive-oriented team to a Super Bowl.

This is where Billick’s massive ego takes over. Not only did he set out to prove that he could keep a team together through a morbid stretch of 21 quarters without a touchdown, he wanted to prove that he could lead them back from a 5-4 start and a three-game losing streak. With a quarterback he picked up off the scrap heap. With a departure in the offensive philosophy. With a rookie running back who punished defenders for four quarters.

Running back Jamal Lewis had already been terrorizing defenses through the first nine games. After injuring his arm on his first carry of a scrimmage against the Redskins in Landover early in training camp, on July 28, 2000, Lewis needed time to mend and didn’t see a lot of action during the preseason. He was behind before he began because of the injury.

“It was a big setback but I think it was a blessing in disguise. I just had to bounce back off of it and just sit back and watch the team and just learn from it,” Lewis told me at The Barn on Sept. 25, 2000. “I think I learned a lot, just getting mental reps and coming along slowly. I think Coach Billick wanted to bring me along slow, but I don’t think I lost a step because of it.”

Coming into the season it was clear that he would be sharing the running load with veteran Priest Holmes. Despite the obvious competition over carries and playing time – it was clear that only one of them could play at a time – a wonderful friendship was forged between the two.

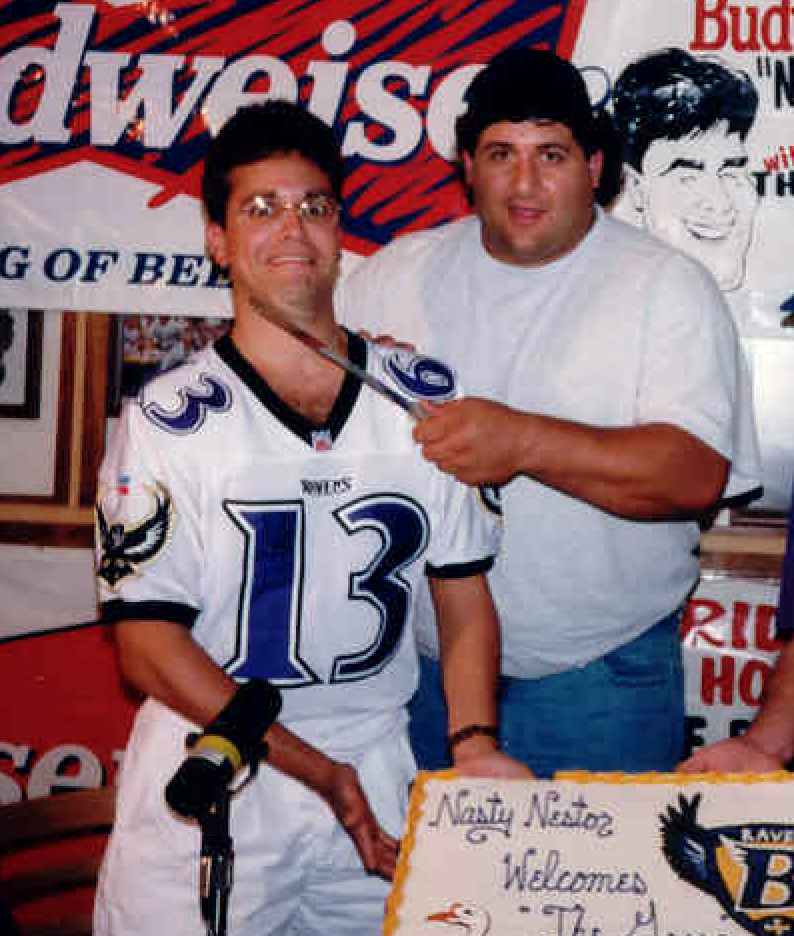

Holmes, a deeply religious man who always has a friendly demeanor toward teammates, media and fans alike, took Lewis under his wing and became an on-the-job mentor for the rookie from Tennessee. The two spent countless hours in each other’s homes watching film during the week and became the best of friends. When Holmes won the “Nasty Nice Guy Award” in November 2000 – my radio show and station began giving the award to deserving sports figures in 1997 at a charity banquet to benefit the Ed Block Courage Awards Foundation – it was Lewis who gave a dedication speech about his competitor and teammate.

“Before every game we go through blocking schemes and what I should do in every situation and everything I need to prepare for,” Lewis told me. “He’s like a player and coach. You know Coach (Matt) Simon (the Ravens’ running backs coach) has to do his job but Priest stays on me pretty much the whole game.”

When he wasn’t running the ball himself, of course.

While Lewis broke in slowly early in the season, Holmes racked up 119 yards on 27 carries in the opener against Pittsburgh and 54 more yards against Jacksonville in Week 2. But after that, it was clear that with a healthy Lewis in the backfield, the workload would change. Lewis’ 76-yard breakout against Miami on just nine carries planted the seed for Billick that Lewis would be more than a lightly used rookie.

Offensive coordinator Matt Cavanaugh saw the progression early in the season and predicted the emergence of Lewis.

“Lewis is a powerful back who has explosion,” Cavanaugh said at the time. “Priest is an explosive back. I’m not knocking Priest. He’s done an excellent job. But the guy (Lewis) was the fifth pick in the draft and he’s got a lot of potential and we’ve got to start using him more. I’m anticipating what sometimes might be a zero run can turn into a 2-yard gain, what might be a 3-yard gain might be a 5-yard gain. And if that’s what happens, it helps us.”

Even through the burn of “The Drought,” Lewis emerged as a force, one that perhaps the Ravens should and could have relied on more. He had 116 yards on 25 carries the first time out against Cincinnati but then started seeing the ball less as Banks and Billick opted for the home run ball. He carried 13 times for 86 yards against Cleveland. Against Jacksonville and Washington, he touched the ball just 16 times each – for 43 and 34 yards, respectively. The Tennessee game was no better, with 17 carries netting him 58 yards.

It was during the Pittsburgh game – the first that Dilfer had a full four quarters to lead the team – that Billick started relying on his horse in the backfield. Lewis carried the ball 19 times for 93 yards in that final loss of the season.

“Jamal combines the rare combination of true explosiveness with sheer power,” Billick said at the time. “I perceive Jamal to be someone who’s going to crank off a couple of 30, 40 and 50-yard touchdowns, and also be that guy you can pound in there from the 20 down in.”

On Nov. 5, 2000, headed to play a dreadful Cincinnati team at Paul Brown Stadium, with an offense struggling for a touchdown worse than any in the history of the NFL, Billick would divert from everything he’d ever known as an NFL coach, everything he’d ever taught.

Billick had taken on all sorts of little pseudonyms as a coach in the NFL. The media dubbed him a “quarterback guru,” “the greatest offensive mind in the league,” and “the architect of the quick-strike offense.”

With Trent Dilfer at the helm and the greatest defense in the history of the game working its magic, Billick would make more than just a subtle change in offensive philosophy. He would be become an offensive mastermind who ran before he passed, reversing every axiom he’d ever known in the NFL.

He called it, quite simply, moving to “The Dark Side,” a tongue-in-cheek reference to the Star Wars movies.